A scientific paper, published in the respected journal Nature Geoscience, shows that our previous estimates of how the Earth's atmosphere would respond to mounting carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations were highly conservative. In fact, the team behind the new investigation says, it may be that the atmosphere is 30 to 50 percent more sensitive to CO2 levels than originally thought. If that indeed turns out to be the case, then we could be looking at the worst consequences even faster than scientists first predicted. The paper also shows that land-ice and vegetation play a huge role in this correlation as well.

In the long run, these two factors have the ability to considerably influence the way our atmosphere responds to CO2 levels. If the former were intact, then we probably wouldn't have anything to fear. But, as it stands, they are not. The ice caps are melting, both at the poles, and in Greenland, and mountaintop glaciers are receding too. On the other hand, forests continue to be cut down, and some of them have already been reduced to arable land, which is used for agriculture or growing animals.

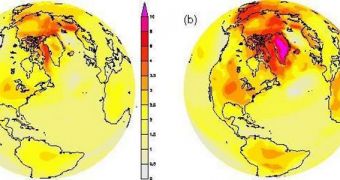

“We found that, given the concentrations of carbon dioxide prevailing three million years ago, the model originally predicted a significantly smaller temperature increase than that indicated by the reconstructions. This led us to review what was missing from the model,” University of Bristol scientist Dan Lunt, the team leader for this research, explains. He says that vegetation and ice mass regulate the amount of sunlight hitting our planet, and getting trapped on the surface. In the case of ice caps, they act like giant mirrors, which reflect light and heat back into the sky.

“If we want to avoid dangerous climate change, this high sensitivity of the Earth to carbon dioxide should be taken into account when defining targets for the long-term stabilization of atmospheric greenhouse-gas concentrations,” University of Leeds expert Alan Haywood, also a coauthor of the new paper, says. “This study has shown that studying past climates can provide important insights into how the Earth might change in the future,” Lunt concludes, quoted by ScienceDaily.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //