Scientists at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) have recently managed a breakthrough in understanding how the human brain makes sense of the physical world around it. They compare the process to navigating the planet using Google Maps. For a general overview, a default map works. But, when you get down to the details, a specific map of the area needs to be loaded, and the view switched from one map to the other. Apparently, our brains are also able to create multiple, independent maps, which it then uses to make sense of things, AlphaGalileo reports.

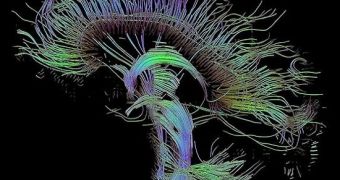

These internal maps, which scientists at the NTNU Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience have been studying for the past four years, are created via so-called grid cells, in a coordinate system. This enables the human brain to produce not only one, but a multitude of smaller maps, some of which present only the rough details, whereas others are extremely accurate. Accompanying these maps is a very advanced sorting system, which, no doubt, took its time to evolve over millions of years.

“We long wondered if all of the brain’s mapping information was stored in a single map. So we figured out a way to check this,” Dori Derdikman, a postdoctoral researcher at the university, says. In their experiments, the researchers analyzed the brains of captive rats, which were allowed to roam freely inside an enclosure. Measurements determined precisely how the rodents' grid cells mapped out the area, and then scientists switched the environment, by adding walls inside the compartment and turning it into a long, narrow maze.

“When the walls were inserted, something happened with the rats’ maps. First we recorded the same map. But when the rats came around a hairpin turn in the maze, the map changed totally. It happened several times, each time in connection with when the rats went around a wall and came into a new corridor,” the scientist adds. The team also discovered that border cells, a recently found type of cells, might play a huge role in associating the maps in the rodents' heads with each individual wall.

“Maybe these border cells are what signal the brain that to [sic] switch maps when you move over a border in your environment. We think that there is this kind of environmental change when the rat enters a new corridor in the hairpin maze,” Kavli Institute expert and team member Trygve Solstad adds. These maps, the researchers conclude, are stored in one of the best protected areas of the brain, the entorhinal cortex, which has remained roughly unchanged for many years.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //