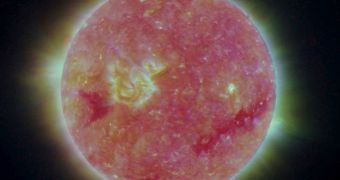

A team of investigators from the United States discovered that about 33 percent of all solar eruptions happening on the Sun are not easily detectable beforehand, and therefore can be described as sneak attacks. The research was conducted with data from the NASA STEREO spacecraft.

While in the past solar storms were always a surprise, and considered to be a random phenomenon, today we have a variety of space probe and solar observatories keeping an eye on our star.

These instruments can detect telltale signs of upcoming solar eruptions, such as flares, coronal dimming, and filament eruptions. When these events take place more often than usual, this is usually a sign that a solar storm is on its way.

Instruments such as the NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) are our main line of defense against such events.

When important solar emissions take place, they emit vast amounts of electrically-charged particles in the Sun's surroundings, at speeds exceeding 1 million miles per hour. When they particle streams reach our planet, they can have negative repercussions.

They can fry electrical components on satellites in orbit, endanger the lives of the crew aboard the International Space Station, and destroy power grids on the surface of the planet.

The very point of having the solar telescopes in place is to prevent that from happening. These sensors can see the solar emissions when they are produced and give us days of forewarning.

But the new investigation, conducted by experts at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), shows that about one third of coronal mass ejections (CME) cannot be detected by checking exclusively for the aforementioned indicators.

“If space weather forecasters rely on some of the traditional danger signs, they'll miss a significant fraction of solar eruptions,” explains CfA expert Suli Ma.

In the new study, she and her team looked at STEREO data covering 24 eruptions that spanned 8 months. The researchers used this instrument because it is made up of two components.

Two satellites orbit the Sun trailing each other, providing a 3D, or stereo, image of the Sun and the processes taking place on its surface.

While peering through the data, the investigators realized that 11 of the 34 CME were not “announced” by either flares, coronal dimming, and filament eruptions.

“Meteorologists can give days of warning for a hurricane, but only minutes for a tornado. Currently, space weather forecasting is more like tornado warnings,” says CfA astronomer Leon Golub.

“We might know an eruption is imminent, but we can't say exactly when it will happen. And sometimes, they catch us by surprise,” he goes on to say.

“The Sun is entering its stormy season, ramping up toward its next period of maximum activity in 2013 and 2014. The more we learn and understand about it now, the better,” Ma explains

Details of the investigation can be found in the October 10 issue of the esteemed Astrophysical Journal.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //