A collaboration of investigators from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Harvard University announces the discovery of the oldest known ciliate fossils. These remnants belong to a class of microorganisms that currently comprises of about 7,000 species.

The most commonly-known ciliate is the paramecium, which is studied even in high school classes. While organisms such as this one are extremely common in watery environments, very little was known about their actual age, until now.

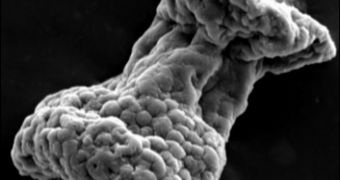

In other words, scientists had no idea when the lifeforms developed, and when they began to spread and cover the Earth. Ciliates differentiate themselves from other, similar microorganisms through the fact that they are single-celled blobs covered in tiny hairs called cilia.

Scientists have been trying to determine when ciliates first appeared for years, but their search has been hampered by the fact that these lifeforms have no solid parts. This means that they fully disintegrate into the environment after they die.

This is why the latest findings by the MIT/Harvard team are so important. Experts with the group managed to discover rare, flask-shaped microfossils of these creatures, which they determined to date back between 635 and 715 million years.

These remains predate the oldest known until now by more than 100 million years. What this implies is that life on Earth was more complex earlier on than initially determined. In fact, it could be that organisms such as ciliates were the precursors of multicellular life.

“These massive changes in biology and chemistry during this time led to the evolution of animals. We don’t know how fast these changes occurred, and now we are finding evidence of an increase in complexity,” says researcher Tanja Bosak.

She holds an appointment as the MIT Cecil and Ida Green Career Development assistant professor, at the MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. Details of the research appear in this week's issue of the esteemed scientific journal Geology.

Researchers are now starting to consider the idea that maybe these microorganisms also played a role in the appearance of vast volumes of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere, as well as in a host of other processes that may have made it easier for complex life to develop.

In the future, experts plan to conduct more studies, aimed primarily at discovering other microfossils. This could give them a clearer image of what the world's oceans looked like millions of years before the Great Oxygenation Event that set the stage for the development of modern life.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //