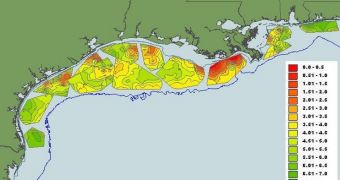

Even without the current oil spill affecting the Gulf of Mexico, the area is very polluted on its own. Every year, waves of agricultural and human runoffs are spilled into its waters from the Mississippi Basin, creating so-called “dead zones.” In these areas, animals either flee or die, and the regions stretch for tens of miles in all directions. Now, with the massive oil slick covering a huge swath of the Gulf's surface, researchers wonder as to how the two phenomena will intermingle, and what the results will be. The answer to this question could extensively benefit the clean-up efforts, ScienceNow reports.

Dead zones grow annually through a fairly simply mechanism. The runoffs hitting the Gulf carry with them high concentrations of nitrogen, a chemical that promotes the development of algal blooms. After the plants die, they naturally sink to the ocean floor, where special bacteria show up to consume them. The issue is that these microorganisms have a very high oxygen intake level, basically taking the chemical out of the water. Without it, fish and other marine creatures only have two options – flee the affected areas or die of suffocation. Several such dead regions developed in the Gulf yearly.

Now, experts say that the oil slick is covering the exact area where oxygen depletion phenomena take place. The investigators are not exactly sure what will happen when the two phenomena will interact. The thing is that both are incredibly complex sets of events, joined together under a single “banner.” Numerous teams are currently on-site, collecting water samples for analysis. Clues derived in this manner could help them figure out what's going on at least partially. There are two main possibilities to consider, the scientists say – either the oil slick will help the dead zones grow, or they will prevent hypoxic regions from doing so.

Small droplets of oil in the water could promote the growth of microbe populations that need oxygen to survive. These microorganisms are capable of feeding on oil, but they have negative effects on marine life. The oil slick could also prevent oxygen from entering the water, further reducing levels. On the other hand, the sheen could also prevent sunlight from penetrating the water, and photosynthetic phytoplankton needs this in order to survive. Blooms could therefore be reduced, starving microbes. The direction in which things will evolve is, however, very fuzzy. “We have no idea right now what's going on,” explains biological oceanographer Nancy Rabalais, who has been studying the dead zones for 25 years. She is based at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium in Chauvin who has studied the dead zone for the past 25 years.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //