Some 251.4 million years ago, the world went through an event informally known as the Great Dying. The massive catastrophe wiped out most of the world's animals and plant species, and now experts are beginning to discover that ocean acidification also played an important role.

The Permian–Triassic (P–Tr) extinction event led to the extinction of 96 percent of all marine species and 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrate species, as well as 57 percent of all families and 83 percent of all genera of insects. This is the only known mass extinction of insects in Earth's history.

There is no single cause for the event. Researchers now believe that a vast interplay of factors led to the natural calamity, and acid is beginning to emerge as an important player. A new computer model indicates that vast amounts of carbon dioxide were emitted into the atmosphere.

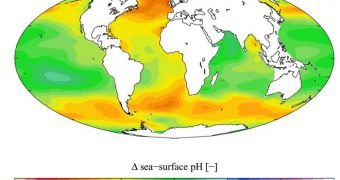

In addition to causing a strong greenhouse effect that heated the planet, the gas also lead to oceanic acidification, as vast amounts were gulped up by the waters and turned into carbonic acid. The same thing is happening now, but on a smaller scale, Science News reports.

“This would have been another stressor in the system that might have pushed things toward extinction,” says St. Francis Xavier University climate modeler Alvaro Montenegro. He and his team published the detailed results of their simulations in the August 2 online issue of the journal Paleoceanography.

Taking into account large CO2 concentrations, of as much as 3,000 parts per million, researchers calculated that the resulting carbonic acid would have led to a decrease in pH to 7.3 in equatorial waters and 7.1 in polar waters.

A lower pH value indicates a more acidic environment, whereas a higher value indicates an alkaline one. Currently, the world's oceans have an average pH level of 8.1, which allows creatures to build their calcium-carbonate shells. An acidic environment prevents this from happening.

“This model may be a reasonable representation of how climate was changing at the time,” comments Stanford University paleobiologist Jonathan Payne, who was not a part of the new investigation.

However, he adds that this theory only holds true if atmospheric CO2 concentrations spiked suddenly, over a short period of time. If the increase was gradual, then the oceans may have found other ways to cope, as would marine life.

Undoubtedly, the extinction would have happened still, but on a much smaller scale. This research therefore provides an interesting framework for other scientists to consider while conducting additional investigations into the P-Tr event.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //