A team of experts led by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) reproductive biologist Jonathan Tilly recently published a new study proposing the existence of stem cells specialized for producing new oocytes (egg cells) in women.

This investigation essentially turns conventional medical wisdom concerning human reproduction on its head. At this point, most scientists working in the field are convinced that women are born with all the eggs they will ever have, whereas men continuously produce reproductive cells.

Tilly has been involved with this line of work since 2004, when he first proposed the existence of reproductive stem cells in women. His ideas were not taken too seriously by colleagues, but the new study provides compelling evidence for his point of view.

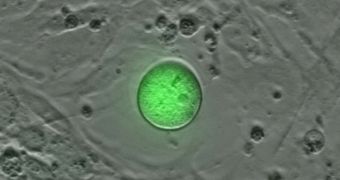

The MGH team was recently able to isolate a number of extremely rare stem cells from ovarian tissue sampled from adult women. When placed inside a culture medium in the lab, the cells differentiated into immature oocytes, Science Now reports.

The discovery is very important for the future of fertility treatments. Therapies meant to help women have children could for instance be focused on promoting the health of these stem cells, rather than on hormones and other molecules, as is currently the norm.

One thing that experts in the international scientific community are certain of is that this debate is far from over. Most likely, discussions will rage on for the foreseeable future, but the prospect that Tilly and his group at MGH propose is very interesting.

According to the expert, the newly discovered oogonial stem cells (OSC) occur rarely in the ovaries, about once out of every 10,000 ovarian cells. But OSC grow very fast in the lab, and certain conditions make them turn into oocyte-like cells spontaneously.

Tilly will continue investigating OSC, first concentrating on discovering or developing chemicals that promote the cells' growth and development. Once this objective is reached, scientists can begin to think about using this cell population for fertility treatments.

Analysts expect a number of reviews to be carried out on the new MGH study. Investigators from other universities will try to replicate the process through which Tilly and his group obtained the OSC.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //