A team of investigators from the Washington University in St Louis School of Medicine (WUSM) has just discovered a new way to go about understanding the patterns of electrical activity in the brain.

When analyzing the functions of the brain, researchers usually keep in mind two very important things – when the activity takes place, and where. This combined approach allows neuroscientists to link various areas of the brain to specific types of events.

But what the research team is now saying is that they can add a third factor to this mix, and that the factor is the precise frequency at which the activity patterns unfold. The discovery sets the stage for new and amazing discoveries to come.

Researchers will soon be able to draw new insights into how the mind functions, and also into the factors that make it function the way it does.

“Analysis of brain function normally focuses on where brain activity happens and when. What we’ve found is that the wavelength of the activity provides a third major branch of understanding brain physiology,” explains Eric C. Leuthardt, MD.

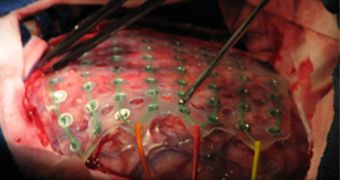

Together with other neurosurgeons, the team analyzed test subjects' brains using electrocorticography, a monitoring method that relies on the use of a grid of electrons. This array is put directly on the surface of the brain, as this provides clearer access to electrical signals flowing through neurons.

According to experts, conventional brainwave monitoring, such as electroencephalography (EEG), can't pick up even a fraction of the signals ECG can.

“We get better signals and can much more precisely determine where those signals come from, down to about one centimeter,” explains Leuthardt, who is a WUSM assistant professor of neurosurgery, biomedical engineering and neurobiology.

“Also, EEG can only monitor frequencies up to 40 hertz, but with electrocorticography we can monitor activity up to 500 hertz. That really gives us a unique opportunity to study the complete physiology of brain activity,” he goes on to say.

Leuthardt and his team already made some interesting findings about how the brain may be varying the frequencies at which its signals get passed on. Those studies were conducted on anesthetized patients.

“Certain networks of brain activity at very slow frequencies did not change at all regardless of how deep under anesthesia the patient was,” the expert explains.

“Certain relationships between high and low frequencies of brain activity also did not change, and we speculate that may be related to some of the memory circuits,” he adds.

The work, which was published in the December issue of the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was sponsored by the Doris Duke Foundation and the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //