For a long time, anthropologists and biologists have tried to understand what exactly is it that prevents our dogs and monkeys, for example, from learning how to read or speak. If brain structures are similar, then why cannot these animals use them more efficiently, and more closely to our own parameters? A new scientific hypothesis proposes that the difference appears at the cortex level, the outer layer of nerve cells covering the brain. The idea argues that cortical modules, small nerve cell ensembles on the cortex, are directly responsible for how much we can learn, a process called “cognitive plasticity.”

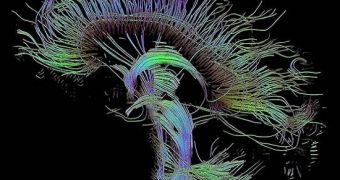

“What [constrains] an individual organisms' ability to learn cognitive skills is essentially the diversity and number of [cortical] modules they have. So, if you think about it like a set of Legos, if you have more Legos, you can build a wider variety of things,” Psychologist Eduardo Mercado III, an expert at the University of Buffalo, in New York, explains the theory. He also reveals that these modules are very evenly spread out all over the brain, in a pattern similar to a honeycomb, LiveScience informs.

Over the years, many biologists have argued that the most decisive factor in determining an organism's level of intelligence is the size of the brain itself. In keeping with the new idea, it's not the size that is responsible for higher levels of cognitive plasticity, at least not directly. By being larger, the cortex allows for more cortical modules to form, a process that some experts believe to be the main “engine” behind improved brain skills and abilities.

Mercado also believes that the distribution, size and shape of these modules may be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Otherwise, it's difficult to explain why rats are smarter than cows, despite the fact that an entire rat's body could fit in a cow's brain cavity. “From birth you have genetic codes that are determining essentially the gross number that you have, so that's sort of a rough guide,” the expert says.

Details of the new theory appear in the latest issue of the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //