A group of investigators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, were recently able to gain a deeper understanding of how water begins to condense at the nanoscale. The work has important practical applications, especially in energy production.

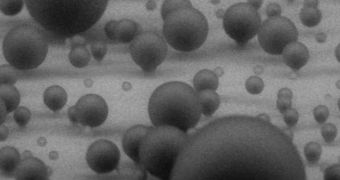

Water has its own speed at which it forms droplets at the nanoscale, but the team was interested in developing a way of boosting that process. They learned that etching specific patterns on the top layer of collecting surfaces could lead to nanoscale droplets forming considerably faster.

Though this process does not seem meaningful in any way at first, it is in fact crucial to the functioning of numerous power plants today, regardless of whether these installations are fueled by fissionable materials, coal, oil or natural gases.

Droplet formation is also very important for the desalinization of seawater. But the scientific theories on which all of these devices and processes are based are not yet complete. In other words, scientists don't really know too much about the factors governing water condensation at these levels.

Details of the research effort were published in the latest issue of the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano. The paper was authored by mechanical engineering graduate student Nenad Miljkovic, postdoctoral researcher Ryan Enright and associate professor Evelyn Wang, all at MIT.

Some physicists used to think that they knew everything there was to know about how water condenses. That may have been the case in the past, but the emergence of advanced technologies – including micro- and nano-patterning – changed all that.

Now, the properties of the surfaces on which water forms nanodroplets are becoming critical to the overall process. The most important trait is wettability, which dictates the behavior of water on any given surface.

This investigation was made possible through the support of the MIT S3TEC Center. The organization is part of a US Department of Energy (DOE)-funded Energy Frontier Research Center.

Researchers now want to move on to computer modeling, in an attempt to create surfaces that could handle the condensation of water into nanodroplets in patterns that are useful for practical applications.

In the long run, this study could translate into a large number of cost-saving improvements to existing technologies being translated into practice, as well as into the development of entirely-new devices.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //