A collaboration of chemists at the Stanford University announces the development of a new class of compounds, which they say are extremely effective at activating the hidden reservoirs of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) the pathogen creates upon infecting the human body.

The new compounds are called bryologs, and they are derived from certain tiny marine organisms, the researchers say. They add that, without activating the hidden HIV reservoirs, it is nearly impossible for other therapies or drugs to wipe out the viral infection.

The main form in which HIV manifests itself is AIDS, the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Thanks to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the condition is no longer a death sentence, as it was decades ago. But these drugs only prolong life, they do not treat the actual causes of the disease.

Currently, AIDS patients need to stick by an extremely rigorous treatment if they want HAART to succeed. This can be very cumbersome and demanding at times, and contributes to reducing patients' quality of life.

Another aspect of this issue is that AIDS is difficult to treat even in the United States, let alone in Africa and other parts of the Third World. Therefore, scientists need a more permanent approach to treatment, one that would remove HIV's proviral reservoirs from the human body.

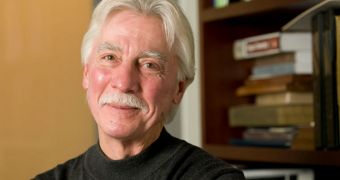

“It's really a two-target problem, and no one has successfully targeted the latent virus,” explains Paul Wender, a chemistry professor at Stanford. He is part of a research team that appears to be getting closer to such a two-step approach to treating HIV infections.

The collection of bryologs his lab developed are very effective at activating dormant HIV deposits, potentially providing a way for other investigators to take this work further. Details of the research effort appear in the July 15 issue of the top scientific journal Nature Chemistry.

“I receive letters on a regular basis from people who are aware of our work – who are not, so far as I know, scientifically trained, but do have the disease. The enthusiasm they express is pretty remarkable. That's the thing that keeps me up late and gets me up early,” Wender explains.

Scientists were supported during this investigation by grant money from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //