A new model developed by researchers at the Princeton University holds the promise of being able to fairly distribute the burdens of carbon dioxide cut responsibilities to all nations that will participate at the December United Nations summit, to be held in Copenhagen, Denmark. Previous proposals have all been rejected by developing and developed nations alike, on the basis that they were unfair and inequitably distributed these responsibilities. The new method for distributing the efforts is so fair, that its creators have hopes of it being considered in the UN summit.

“Our proposal moves beyond per capita considerations to identify the world's high-emitting individuals, who are present in all countries,” the team explains in an introduction to the presentation of its model, published in this week's online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The idea that the authors have now set forth was, in a form, presented in the 2006 documentary “An Inconvenient Truth,” produced by former US Vice President Al Gore. Among the paper's authors are the PU Frederick D. Petrie Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Stephen Pacala, and PU Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Robert Socolow.

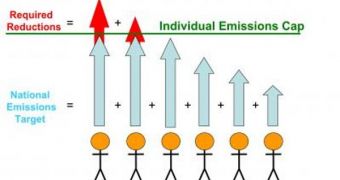

The reason why the new proposal is so fair, the researchers say, is the fact that it relies on using individual emissions as the basis for its calculations, rather than the average amount of pollutants a country emits during one year. In the later version, which has been labeled as unfair by many countries around the world, the pollution that is created by the large industry goes largely masked by the overall average. With the new model, the largest emitters of greenhouse gases will be singled out, and then the burden of accounting for the pollution they emit will fall squarely on their lap, and not on the shoulders of the general public of a specific nation.

“Most of the world's emissions come disproportionately from the wealthy citizens of the world, irrespective of their nationality. We estimate that in 2008, half of the world's emissions came from just 700 million people,” Shoibal Chakravarty, a physicist at the Princeton Environmental Institute, and one of the lead authors of the new paper, explains. “The team worked together to formulate a novel approach to a long-standing and intractable problem,” Pacala adds.

“UN rules and customs make it difficult for the international community to examine what is going on inside countries. That's probably why our simple proposal based on individual emissions has not emerged from the diplomats. Over the next several decades, global environmental rule-making will need new wisdom to accommodate developing countries whose per capita data belie the presence of both large populations of the very poor and upper and middle classes that are major consumers of resources. Our proposal is a start down this road,” Socolow concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //