A-H1N1 is the influenza strain that is responsible for the current swine flu pandemic, which has already stretched across the world and claimed thousands of lives. Although it carries a higher degree of danger as opposed to the “standard” strains, it is not unlike them in the way it acts. That is to say, it can be fought off during the first days after infection, using average drugs such as Tamiflu. However, after the incubation period, the virus multiplies out of control, and becomes too much of a load for a single medicine to treat. That's why researchers are currently seeking to take a new approach in fighting this invader, Technology Review reports.

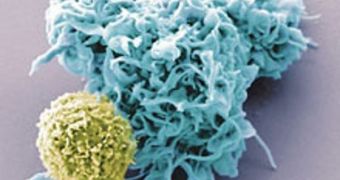

Rather than attempting to destroy the viral cells one by one using a drug, the experts are looking to create a method of rallying the entire immune system against the pathogen. Such an all-out attack will be overwhelming, even for the massive number of viral cells that influenza strains are known to produce. The single issue now is finding the best possible method of activating the required immune system cells, and also of steering them in the correct direction. An overblown immune response that has nothing to pick on can be extremely hazardous to a patient, experts caution.

This is one of the main reasons why the LEAPS (Ligand Epitope Antigen Presentation System) was created at the Vienna, VA-based company Cel-Sci. The system is extremely important for the new effort because it is capable of doing a unique thing, and that is detect epitopes. These structures are tiny pieces of the virus itself, which give researchers clues as to which immune reactions would be best fitted to destroy the pathogen. In other words, the viral agent itself is giving the researcher clues on how to destroy it. This is what makes this method so innovative, scientists at the company reveal.

What the team does next is engineer the epitopes in the lab, and attach them to ligands, materials that bind specifically to certain immune cells. This means that the viral fragments are taken directly to a specific type of immune cells (whichever doctors select), and make them aware of the virus' presence. The immune system's natural response then takes over, as all types of defending cells communicate with each other through specific channels, which are not affected by the virus. “It's like a live virus vaccine – and more effective – but without the live virus,” Kenneth Rosenthal, a scientist who collaborated with the Cel-Sci team, explains. He is also an immunologist at the Northeastern Ohio University Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //