A group of scientists at the Cambridge-based Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announces the creation of a new technique for turning seawater into potable water. They use graphene as the primary filtration material in this approach.

Graphene is a single-atom-thick carbon compound, which features a hexagonal atomic arrangement, and displays an impressive series of physical and chemical properties. Scientists used to believe that the stuff would be helpful for the electronics industry, but other applications are beginning to crop up, too.

This advanced material – which was first obtained from graphite back in 2004 – will be used as the filtration material in a new desalination technique developed at MIT. The reason why a new material was needed is that existing desalination technologies are too expensive to implement widely.

As the world's population increases, the accelerated growth is placing huge strains on Earth's freshwater supply. Therefore, experts need to tap into the nearly endless supply of saltwater from the world's oceans.

The graphene-based approach promises to be less expensive and more efficient than any desalination systems currently available on the market. Details of how it works were published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific journal Nano Letters.

The senior author of the paper was the MIT Department of Materials Science and Engineering Carl Richard Soderberg associate professor of power engineering, Jeffrey Grossman. “There are not that many people working on desalination from a materials point of view,” he says.

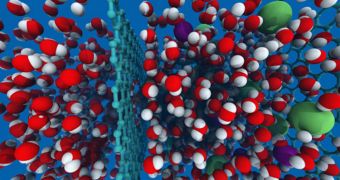

Working together with lead paper author and MIT graduate student David Cohen-Tanugi, Grossman produced carefully modified sheets of graphene, which feature holes of specific dimensions, spaced out at regular intervals.

The team also doped (added other substances to) the graphene, outfitting these holes with chemicals that were either hydrophobic (water hating) or hydrophilic (water loving). Grossman says that he was not expecting the carbon compound to be so effective at desalination.

At this point, the MIT team only has a few simulations of the new material in place. However, by the end of the summer, the researchers plan to begin real-life simulations of their new technique, and assess whether it can be scaled up to the levels where it could be used to alleviate global water shortages.

“Manufacturing the very precise pore structures that are found in this paper will be difficult to do on a large scale with existing methods,” comments Haverforf College assistant professor of chemistry, Joshua Schrier.

But “the predictions are exciting enough that they should motivate chemical engineers to perform more detailed economic analyses of […] water desalination with these types of materials,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //