A team of experts has recently developed a new chemical compound, that could in the near future be used to bin chloride ions, but with a twist.

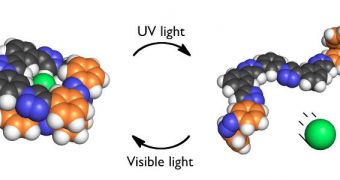

According to its creators, while the new molecule is especially suited at engulfing the ions, it can also be made to release them upon demand, by simply shining ultraviolet (UV) light on it.

The new substance was made by chemists at Indiana University Bloomington, PhysOrg reports. Details of how it functions are published in the August 30 issue of the top-rated Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS).

“One of the things we like most about this system is that the mechanism is predictable – and it functions in the way we propose,” explains Amar Flood.

Flood is a chemist at IU Bloomington, and also the leader of the new research effort. He conducted the work with PhD student Yuran Hua.

The work was conducted on chloride because this is one of the most common chemicals on the planet. It can be found anywhere from seawater to the bodies of all living creatures.

“We have two main goals with this research. The first is to design an effective and flexible system for the removal of toxic, negatively charged ions from the environment or industrial waste,” Flood says.

“The second goal is to develop scientific and even medical applications. If a molecule similar to ours could be made water soluble and non-toxic, it could, say, benefit people with cystic fibrosis, who have a problem with chloride ions accumulating outside of certain cells,” he adds.

As such, the new development could be used to great practical advantages in a new series of medical therapies, aimed at a variety of conditions.

“That's the direction we're headed. It actually wouldn't be that difficult to modify the molecule so that it is water soluble. But first we need to make sure it does all the things we want it to do,” Flood adds.

He explains that his specialty is in designing molecular machines that serve a single purpose. One of the main goals is to push the boundaries of what can be done in laboratories further and further.

“A lot of the ideas in our paper have been floating around for some time. The idea of a foldamer that binds anions, the idea of a foldamer that you can isomerize with light, the idea of receptor that can bind anions,” the team leader explains.

“But none of the prior work uses conductivity to show that the chloride concentrations actually go up and down as intended. What's new is that we've put all these things together. We think we have something here that allows us to raise our heads to the great research that's preceded us,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //