A group of engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge announces the development of a new type of vaccine that can elicit a very strong immune system response. This study could lead to the development of new ways of counteracting the world's most dangerous diseases.

The most common type of vaccine out there today is the one featuring killed-off or inactivated versions of a particular virus. These therapies are used for infections such as polio, influenza and measles, but are simply too risky, or too ineffective, to be used for more dangerous conditions.

An alternative to an inactivated virus vaccine is a small protein fragment vaccine. Such a therapy features snippets of molecules that are only produced in the body when a specific infection occurs. The problem with these vaccines has until now been that they did not create a very strong immune response.

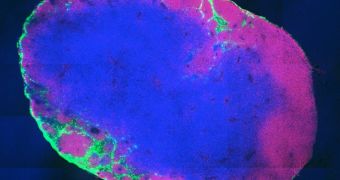

What the MIT team did was figure out a way of delivering these vaccines loaded with protein fragments into lymph nodes – the headquarters of vast numbers of immune system cells – via a molecule in the human body. Early trials on mouse models have revealed that the approach is very effective.

The new class of vaccines is able to latch on to the protein albumin, and thus hitch a ride through the bloodstream, all the way to the lymph nodes. The team says that this transport mechanism ensures that the immune system exhibits a very strong response to the stimuli, producing relevant antibodies.

Details of the new investigation were published in the February 16 online issue of the journal Nature.

“The lymph nodes are where all the action happens in a primary immune response. T cells and B cells reside there, and that’s where you need to get the vaccine to get an immune response. The more material you can get there, the better,” comments the senior author of the paper, Darrell Irvine.

The expert holds an appointment as a professor of biological engineering, materials science, and engineering at MIT, and is also a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. He says that these new vaccines could work particularly well against AIDS and cancer.

“This lymph-node-targeting modification causes pretty much all of the material to get caught in the draining lymph nodes, so that means it’s more potent because it’s getting concentrated in the lymph nodes, and it also makes it more safe because it’s not getting into the systemic circulation,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //