Since 2004, the NASA/ESA space probe Cassini has delivered amazing new information about the system that is Saturn and its moons. A whole range of phenomena were finally explained using models created from these datasets, while other mysteries deepened the more investigators looked at them. But Cassini managed to make some important discoveries of the moons Titan and Enceladus, among others, such as the fact that the second features geysers on its surface, whereas the first has lakes of liquid hydrocarbons at its poles. Now, a new image gives us an additional insight into Enceladus.

This particular moon is very weird, astronomers say. A crust of ice is known to cover its surface, but the spacecraft has determined that cracks in this layer let out spews of water and ice vapor. Scientists have thus far been able to determine that a warming effect which periodically takes place inside the moon tends to warm some of the ice inside, which eventually rises to the surface, and is released through the cracks. Cooler ice falls down to the core and the process picks up again. But many believe that the belly of Enceladus holds an ocean of liquid water, which may even be capable of supporting basic life.

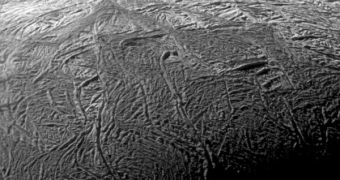

Cassini snapped a new set of photos of the Saturnine moon during a November 21, 2009 flyby, and the American space agency has now released these images to the general public. They reveal the erupting geysers in exquisite detail, and have even allowed experts to determine that some of the eruption sites are losing power. The advantage of having a long-term orbital mission, managers say, is that you can keep an eye on how ongoing phenomena evolve over time. This gives planetary scientists and geologists a clearer indication of the processes that may be at work in determining the eruptions.

“This last flyby confirms what we suspected. The vigor of individual jets can vary with time, and many jets, large and small, erupt all along the tiger stripes,” says the leader of the Cassini imaging team, Carolyn Porco. She is an expert at the Boulder, Colorado-based Space Science Institute. The scientist reveals that many of the new images are in fact composites, created by combining two or more high-resolution photos snapped by the orbiter's narrow-angle cameras. One of these photographs reveals a host of about 30 jets, of which 20 had not been previously seen, Space reports.

“The fractures are chilly by Earth standards, but they're a cozy oasis compared to the numbing 50 Kelvin (minus 370 Fahrenheit) of their surroundings. The huge amount of heat pouring out of the tiger stripe fractures may be enough to melt the ice underground,” says of the possibility of an underground ocean composite infrared spectrometer team member John Spencer, who works at the Southwest Research Institute.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //