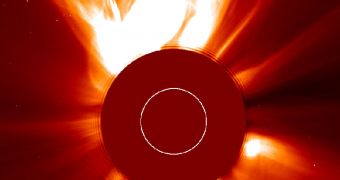

A recent solar flare from our Sun has put the international astronomical community in a state of heated debate, as a team of researchers proposed that the cosmic event proves a long-since abandoned theory that CME are in fact giant ‘magnetic flux ropes.’

This was first hypothesized back in 1989 by Dr James Chen, a scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), in Washington DC. He said at the time that coronal mass ejections were in fact twisted magnetic field lines, which caught on the shape of a donut.

After the idea was proposed, it was abandoned by the international community because other experts felt like it had little merit in explaining what was going on.

In fact, scientists have trying to do that for many years, given that the existence of solar flares was first demonstrated back in 1859. Details of the interactions that take place on the star as this happens are scarce, experts say, and Chen's idea may provide a not-so-new insight into the matter.

When solar flares appear, they force trillions of tons of ionized gas away from the Sun, and this matter takes about a day to reach Earth. It travels at a speed of about 2,000 kilometers per second.

Using the NASA twin Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO), experts have been able to look closely at the Sun in wavelengths that were not accessible before. The violent nature of the Sun is now being revealed in more details than ever before.

With this new capability, it became apparent to researchers that a new CME they saw recently in fact supported the 1989 theory Chen set forth. The new solar activity pattern was modeled on the old idea, and the results matched perfectly.

The expert's theory is a bit more complex than that. It relies on knowledge that the surface of the Sun does not spin at the same speed at all locations. The Equator spins considerably faster than the poles.

This gives birth to twisted field lines, as the varied rotation speed causes plasma to move and drag the magnetic field lines with it. Once a certain threshold is reached, the lines burst up into the donut-shaped structures we know as CME.

Using this idea, STEREO data, and a computer model, Chen and George Mason University PhD student Valbona Kunkel discovered that the theory was very efficient in predicting the trajectory that the CME took once it began developing.

The new data could be used to develop better defense strategies against powerful solar flares, which can endanger crews on the International Space Station, fry satellites, cause auroras, and melt electrical components in power grids, Universe Today reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //