A team of scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, led by electrical engineer Ahmed Kirmani, announces the development of an advanced type of camera that is capable of producing three-dimensional images of various objects in near-absolute darkness.

As a rule, photography needs as much light as possible. The more light is available to record an object or a landscape, the higher the chances of the photo turning out very good. However, the MIT team decided to create a new solid-state detector that takes the dimmest view on things every achieved.

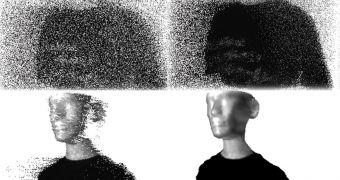

The detector is so sensitive that it can see individual photons with each of its pixels. The information contained on the photons are then analyzed during processing, and the data stitched together to create an incredibly accurate image that features a significant amount of depth.

This innovative device could be used for a variety of applications, such as studying complex and sensitive biological structures. Using normal photography, it is nearly impossible to image the human eye, since its tissues are damaged by intense light.

With the new sensor, it may be possible to look at the eye without illuminating it significantly. In addition, the team says, the research could have applications in tactical law enforcement, espionage and intelligence gathering, in situations where insufficient natural light is available.

The real brain behind this new device is the algorithm developed at MIT, which enables the creation of correlations between neighboring parts of an illuminated object, all while adhering to a strict understanding of the physics of low-light illumination.

The group published details of its investigation in the November 28 issue of the top journal Science, Nature reports.

“The paper illustrates some remarkable examples of this new computational imaging technique and could point a future direction for a number of single-photon depth imaging approaches,” comments Gerald Buller, a photonics expert at the Heriot-Watt University, in Edinburgh, who was not a part of the new research.

Kirmani says that the new sensor required only about one million photons to create the image you see attached to this article. By comparison, the same image would have required hundreds of trillions of photons to produce, were it snapped with a regular camera under normal illumination conditions.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //