We are more than an odd ape. We are odd as a species due to the fact that we are just one human species. Usually, only living fossils and relicts are represented by just one isolated species. Now, a pair of fossils recently found in Kenya show that once more than just one human species lived side by side.

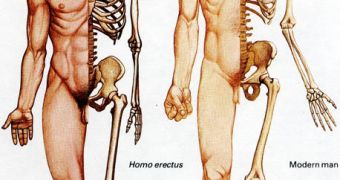

It was believed that there was a successive progression: Homo habilis gave rise to Homo erectus, whose African type, H. ergaster, evolved in modern humans, Homo sapiens. The main difference between H. erectus and modern humans was the brain size, the first having 75 % of our brain size.

But the newly discovered upper jawbone and skull, coming from two separate skeletons, would point to the fact that H. habilis was not our direct ancestor and that H. erectus had a behavior which resembled more that of an ape than previously believed.

The fossils were found by the Koobi Fora Research Project, led by the mother-daughter team of Meave and Louise Leakey from the National Museums of Kenya.

The jawbone is attributed to H. habilis and was 1.44 million years old, while the oldest habilis fossil previously found was 1.8 million years old. It is by far the younger H. habilis and shows the species survived well after the emergence of H. erectus. "The finding indicates the two species lived side-by-side for half a million years in eastern Africa. I'm very cautious saying this, [but] it has the potential to remove Homo habilis from the direct ancestral line to us modern humans" said lead researcher Fred Spoor, a professor of evolutionary anatomy at University College London.

It appears that H. habilis and H. erectus were rather sister species, 2-3 million years old, in a time of scarcity in the fossil record.

"The two species likely occupied different ecological niches, allowing them to co-exist without competing against each other for limited resources. A good analogy is the chimps and gorillas. There are a bunch of places in West Africa where both of them live in the same area. But they don't interbreed, they keep to themselves." said Spoor.

"The common ancestor of H. habilis and H. erectus remains a mystery," he added.

Still, many anthropologists believe that H. sapiens evolved from H. erectus, perhaps via an intermediate species, like H. antecessor or H. rhodesiensis.

"H. erectus may still have evolved from H. habilis, but different adaptations and lifestyles could have allowed some populations to live alongside each other for hundreds of thousands of years." said Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London, not involved in the research.

"One possibility is that the larger and perhaps more mobile erectus species was an active hunter, while habilis scavenged or caught small prey," he said.

The other fossil is a well preserved skull of H. erectus, 1.55 million years old and the smallest H. erectus skull discovered so far.

"The find suggests that H. erectus could vary tremendously in size. One way of reading that is that there is a lot of size difference between males and females, which would be a lot more sexual dimorphism than we previously thought," said co-author Susan Ant?n, an anthropologist at New York University.

"In primates large size differences between males and females can be related to sexual selection, mate competition, and reproductive strategy." she said.

In gorillas, a large male silverback gorilla has several smaller female mates, whereas in the monogamous gibbons males and females are similar in size and shape. Previously, H. erectus was believed to be more like us in terms of size difference between males and females. This shows a sexual competition amongst males and this means a less cooperative behavior than in modern humans.

"If this is sexual dimorphism and a lot of sexual dimorphism, then it's probably telling us something about behavior that was somewhat less like what we are today," Ant?n said.

These fossils "indicate at least two lineages of the genus Homo overlapped in eastern Africa. All of this is really contributing to a picture of diversity in early hominid evolution in this time period. And it's another problem for the notion of linearity. Rather, the history of hominids in this time period was one of experimentation-of different ways to be hominids." said Ian Tattersall, an anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, not involved in the research.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //