Scientists with the Pennsylvania State University (Penn State) announce the discovery of a previously-unknown pathway that enables nerve cells to get repaired following an injury. The effect applies to dendrites, portions of neurons responsible for creating synapses with other nerve cells.

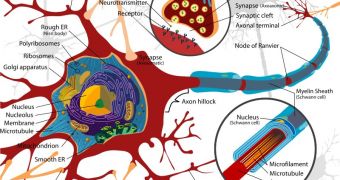

Dendrites are usually located on the body of a neural cell. The projections located at the end of a neuron's tail, or axon, are called axon terminals and display some minor differences, but fulfill the same functions. Dendrites usually bind with axon terminals from neighboring neurons via synapses.

In the new study, the Penn State group determined that dendrites damaged through injury could regrow to at least a portion of their original size. The work also revealed that this improvement occurs relatively fast, within 4 days of the injury. Dendrites can grow by as much as 100 nanometers in this interval.

Details of the research appear in a paper entitled Dendrite Injury Triggers DLK-Independent Regeneration, which is published in the January 30 issue of the esteemed research journal Cell Reports.

This study is important because it is the first ever to demonstrate that dendrites can regrow. Previous investigations have established that only axons can regrow, but said nothing regarding dendrites.

Now that axonal and dendritic regeneration is known to be possible, researchers can start looking at neural regeneration with different eyes. These studies may set the foundation for new efforts aimed at improving recovery rates for patients who have suffered neural damages in their heads or spines.

“For example, if you break your arm and the bone slices some axons, you may lose feeling or movement in part of your hand. Over time you get this feeling back as the axon regenerates,” Penn State associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology Melissa Rolls explains.

The experiments conducted at the university involved researchers cutting dendrites on neural cells in fruit flies. “We wanted to really push the cells to the furthest limit. By cutting off all the dendrites, the cells would no longer be able to receive information, and we expected they might die,” says Rolls.

“We were amazed to find that the cells don't die. Instead, they regrow the dendrites completely and much more quickly than they regrow axons. Within a few hours they'll start regrowing dendrites, and after a couple of days they have almost their entire arbor,” she adds. Rolls was a coauthor on the study.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //