Scientists say that depressed individuals seldom display symptoms exclusively associated with this condition. Most often, they also exhibit other afflictions as well. A new study indicates that people who are depressed are more likely to display neural hyperconnectivity.

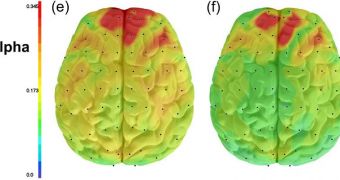

What this means is that they have very many connections between the nerve cells in their brains. These synapses allow various areas of the brain to communicate with each other. It would appear that these connections increase in number and strength during depression.

In other words, the condition may very well be the result of excessive neural activation, scientists at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) explain. Thus far, few investigators took into account the possibility that malfunctioning brain networks may be responsible for depression.

Usually, patients display other symptoms that attract the attention of professionals, such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, the inability to concentrate and pay attention, or the inability to remember things correctly.

What the new investigation managed to demonstrate is that depressed individuals exhibit this type of neural hyperconnectivity between most brain areas, not just those responsible for encoding the aforementioned behaviors.

Details of the new investigation were published in this week's issue of the esteemed journal PLoS ONE, which is edited by the Public Library of Sciences. “The brain must be able to regulate its connections to function properly,” Dr. Andrew Leuchter explains.

“The brain must be able to first synchronize, and then later desynchronize, different areas in order to react, regulate mood, learn and solve problems,” adds the expert, who holds an appointment as a professor of psychiatry at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior.

According to the team leader, it could be that the depressed brain loses the ability to turn off the synapses it creates in order to form functional connections between various areas of the brain. This process takes place regularly, and is very important for optimal cognitive functioning.

“This inability to control how brain areas work together may help explain some of the symptoms in depression,” Leuchter explains. He concludes by saying that this was the largest investigation of this type ever conducted.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //