A group of Japanese experts has recently developed a new mechanism for delivering drugs inside the human body. The method relies on the use of nanoparticles to deliver chemicals inside tumor cells, by sneaking the drugs past the cancer cells' defenses.

The technique was demonstrated to work even on the most drug-resistant types of tumors, the researchers say. If the new treatment option is introduced, then thousands of lives could be saved around the world every year.

Existing therapies against cancer are very harmful for the body as a whole. Radiotherapy subjects people to large doses of radiation, whereas chemotherapy involves taking large amounts of very powerful drugs.

But these chemicals are not selective, in the sense that they do not exert their influence on cancer cells alone. This means that they can, for example, destroy healthy tissue located around a tumor as well.

It has been a long-standing goal in medicine to prevent this from happening as much as humanly possible, and the new, nanotechnology-based approach looks like a promising step in that direction.

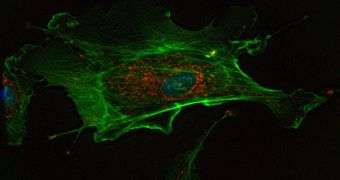

The method was developed by experts at the University of Tokyo, who created nanoscale structures called micelles, that can carry drugs. These formation are basically small soapy clusters of molecules.

The thing about these micelles is that they completely seal the drugs they carry from the inter-cellular medium. Then they harness a cellular transport system to enter the cancer cell. As chemical agents on tumors do not detect foreign, dangerous substances, they let the structures through.

Once inside the cell, the nanostructure carries the drug close to the nucleus of the cell, and then releases it at that location, for maximum effect. If this is done properly, then cellular defense mechanisms won't have time to intervene and stop the chemicals from taking effect.

In studies conducted on unsuspecting lab mice, investigators demonstrated that the growth of tumors could be stopped, even in rodents that were completely unresponsive to the usual variant of an anti-cancer drug.

When the chemical was encapsulated in micelles, it suddenly began to take effect. Details of the research appear in the January 5 issue of the esteemed journal Science Translational Medicine.

“This addresses a key hurdle in cancer treatment by overcoming the limitations faced by free drugs – that is, development of resistance by cells,” explains scientist Samir Mitragotri, quoted by Technology Review.

The expert, who holds an appointment as a professor of chemical engineering at the University of California in Santa Barbara (UCSB) was not involved with the new study.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //