There was a time in astronomy when, if investigators wanted to catch a closer glimpse of a certain phenomenon, they simply had to wait for it again. These days are long gone, they say now, with the advent of modern physics and of the ability to create simulations of these occurrences by using lasers. This was done recently with a multi-trillion-watt laser, an instrument that delivers more power than the entire grid of the United States and which proved capable of simulating what happens when powerful stellar jets collide with gigantic clouds of dust and gas.

The study also marked a very important milestone – the first time new data of cosmic events were collected in the lab, rather than through astronomical observations. The Omega laser, the “star” of this research, was operated by experts at the University of Rochester in New York, whose goal was to determine how emissions from young stars influence the surrounding blankets of gas and dust, such as for example inside a stellar nursery, Space reports. The team then compared the results they obtained in the lab with telescope data and also with the results of complex computer models, on the same issue.

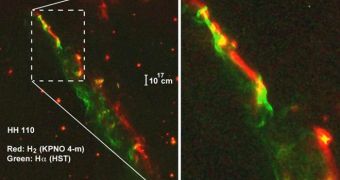

“Ours is the first study to investigate what happens when jets run into obstacles along their paths, and the first to have a strong enough laser to properly scale the shock waves in a jet to the astrophysical case,” explains astrophysicist Pat Hartigan. The expert, based at the Rice University, in Houston, Texas, was also the lead author of the new investigation. “Targets are literally the width of a dime. And then to hit the things with one of the most powerful lasers and not have it all turn into mush, that's what the target design was really pushing,” University of Rochester astrophysicist Adam Frank adds.

The action of young stars is not the only thing that has been modeled by researchers in Earth-based labs. Supernova blast waves have also been simulated using extremely powerful lasers and results were promising. The Omega instrument, which is about the size of a football-field or as large as the entire International Space Station (ISS), is one of the top three most powerful and suited lasers on the planet. The strongest is at this point located at the National Ignition Facility (NIF), in California, where experts want to recreate a star in the lab.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //