Oxygen deprivation can lead to a condition known as brain swelling – or cerebral edema – which seems to have been the culprit in several of the yet unexplained deaths of people escalating Mount Everest, the tallest peak in the world. Thus far, these unfortunate accidents were attributed to Yeti, the snowman, and legends were created around them. Now, researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) found out that the hypoxia was most likely responsible for most of the fatalities that occurred above the base camp of the mountain.

Hypoxia aside, there are numerous obstacles that stand in the way of those seeking to reach the 29,000 foot (8,850 meter) limit. Incredibly strong winds, powerful avalanches, deceiving ice and crevasses, as well as changing weather, are just few of the things that could adversely affect an attempt of reaching the world's highest over-water peak. "Nobody was attacked by any Yeti or anything else," says MGH scientist, Paul Firth.

"Of the guys who died up at 8,000 meters (26,000 feet), a large number of them were developing neurological symptoms. In other words, they were getting confused, comatose or they were having a loss of coordination," argues the researcher, whose finds appear in the British Medical Journal.

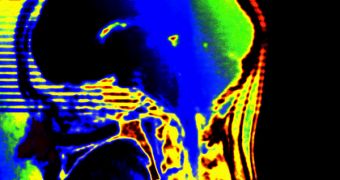

Because of the small amounts of oxygen that enter the brain above 26,000 feet – about a third of the amounts that can be found at sea level – blood vessels in the brain start leaking fluid, which in turn spreads and covers nearby tissue, causing it to swell. Confusion and lack of coordination are two of the main symptoms that occur after that, that's why researchers say that most people who died in the area known as “the dead zone” were actually climbing down the mountain, and not going for the peak.

Statistically, out of all the climbers that ventured at altitudes higher than the base camp of the Everest, 1.3 percent died, due to various reasons, including brain edema. Scientists conducting the new investigation established that a part of those who simply vanished during climb may have fallen victims to brain hypoxia and simply lagged behind, or fell into one of the large crevasses in the ice.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //