A collaboration of researchers at NASA and international university partners is now providing the most extensive and in-depth view on the magnitude 9 earthquake that devastated Japan on March 11, 2011.

The tremor occurred at 2:46 pm Tokyo time (0546 GMT), and was initially classified as a magnitude 8.9. Later reclassified to magnitude 9, it generated a massive tsunami that swept across shorelines, killing thousands, destroying property, and damaging the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Its epicenter was located 80 miles (128 kilometers) offshore, at a depth of 24.4 kilometers (15.2 miles), and around 373 kilometers (231 miles) northeast of the Japanese capital, Tokyo.

As the country is recovering from the disaster, experts are working hard to get to the bottom of what happened, and what the event's consequences will be. The new study was led by researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), in Pasadena.

All details now available on this rare megathrust earthquake event are published in the May 19 issue of the esteemed journal Science Express. The data used were collected by a dense regional monitoring network, which can measure how much the ground moves.

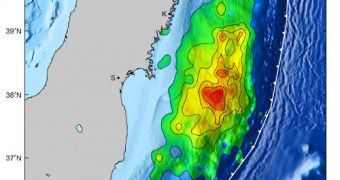

As a result, scientists were able to produce a model of the fault slip, which incorporated GPS data provided by expert Susan Owen, Angelyn Moore and Frank Webb. They are all based at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), also in Pasadena, California.

The study shows that nearly 155 miles (250 kilometers) of fault line ruptured during the earthquake, although only about half of this length was expected to break during an event of this magnitude.

Low-frequency seismic waves produced by the tremor came from the area around the fault slip, whereas the high-frequency waves the team investigated originated much closer to the shorelines.

Scientists add that no one expected the soft-material seafloor around Japan to be able to store as much energy as it did. This earthquake produced a displacement 5 to 10 times larger than though possible in events of this type.

Another important conclusion is that the Pacific and Okhotsk tectonic plates, whose interactions were responsible for triggering the seismic event, were most likely locked in place for as much as 1,000 years, before March 11.

Conducting this study was only made possible by funds provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the US National Science Foundation (NSF), through a number of grants, and the Southern California Earthquake Center.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //