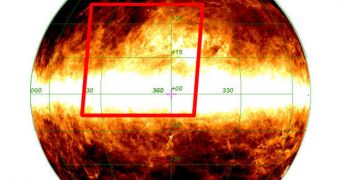

The European Space Agency (ESA) can now be proud of the amazing instrument it is managing. The Planck Space Telescope is undoubtedly one of the most advanced pieces of equipments sent to space, as evidenced by the volume of work that went in it, as well as by the amazing results it is constantly sending back to Earth. In a series of new images, it reveals that amazingly-large filaments of cold gas float through our galaxy, and also provides astrophysicists with new tools of understanding how these forces drive stellar formation, as well as the shape of the Milky Way.

The recently-photographed structures exist within the solar neighborhood, some 500 light-years away from our Sun. These local filaments, as experts call them, are directly tied to the inner parts of the Milky Way, experts at ESA say. The team also determined that most of these emissions came from a very long distance away, from across the disk of the galaxy. The instruments aboard the Planck observatory has determined that some of these filaments feature gas that is as cold as –261 degrees Celsius, only 12 degrees above absolute zero (0 degrees Kelvin). Warmer dust can also be seen in the new images, but it is only located within the plane of the galaxy.

All material that is suspended above or below the galactic plane is cooler. “What makes these structures have these particular shapes is not well understood,” explains ESA Planck project scientist Jan Tauber. Astronomers have dubbed some of the most dense structures “molecular clouds,” while the more diffuse ones have been termed “cirrus clouds.” The new images show only dust, but researchers know from previous investigations conducted with other satellites that both gas and dust make up these structure. What experts have yet to get a grip on is precisely what interactions in the galaxy force these clouds to take on the filamentary patterns.

Some of the processes that have thus far been related to these shapes include cosmic radiation, particles jets from stars and black holes, and magnetic fields. Still, there is currently no way of knowing to which extent each of these phenomena is involved in shaping the clouds. Further studies of the sky, using Planck and other advanced telescopes, could one day provide an answer to this important question, but experts doubt that even the technology on this advanced observatory, and on its cousin Herschel, is sufficiently-developed to allow for such finely-tuned studies at this point.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //