A group of researchers from the University of Michigan in Ann Harbor (UM) announces the creation of a monitoring method for bacteria that eliminates the need for microscopes. Their technique relies on using a device made from components that are commercially available and cheap.

In fact, the team says, their innovation requires a few of the components used in modern-day CD players. What the device does is it monitors the growth and drug susceptibility of individual bacterial cells, all while not using a microscope.

The main implication for this achievement is that researchers will be able to test and see whether bacteria are resistant to new antibiotics in a matter of hours, rather than days, as usual.

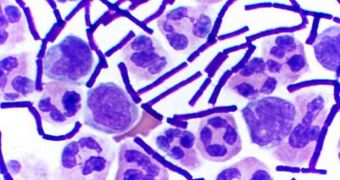

At this point, when new drugs are tested on microorganisms, researchers need to grow culture of the agents first. The process takes a few days, and this is why finding new drugs can be so difficult.

According to UM experts, the new biosensor they developed promises to speed treatment of bacterial infections by several orders of magnitude. This could help improve patient survival rates, reduce healthcare costs and diminish the spread of antibiotic resistance.

The device was developed by a team led by the UM Richard Smalley Distinguished University Professor of Chemistry, Physics and Applied Physics, Raoul Kopelman. The expert is also a professor of biomedical engineering, biophysics and chemical biology at the university.

The team details their new device, called the asynchronous magnetic bead rotation (AMBR) sensor, in the January 15 issue of the esteemed medical journal Biosensors and Bioelectronics.

Former UM graduate student Brandon McNaughton was the brains of the sensor-development initiative years ago, when the instrument was in its earliest stages. The work took place in Kopelman's lab.

“The method can detect growth of as little as 80 nanometers, making it far more sensitive than even a powerful optical microscope, which has a resolution limit of about 250 nanometers,” explains UM graduate student Paivo Kinnunen.

The scientist, who is also one of the lead authors on the new paper, explains that microscopes were used in the proof-of-concept study in order to validate the results obtained by the AMBR sensor.

“You can basically tell, within minutes, whether or not the antibiotic is working,” Kinnunen adds. Soon, “we expect it will be possible to make the determination even quicker,” adds graduate student Irene Sinn.

“This is something we are actively working on,” adds Sinn, who is the other lead author of the paper.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //