The classical concept states that HIV gradually decreases the body's immune ability to fight infection. But a new research proves that this principle is wrong, turning upside-down all the researches in the field.

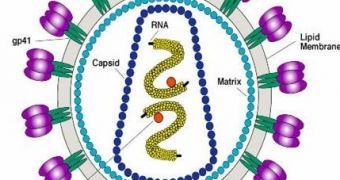

HIV is known to attack the human immune cells called T helper cells. Their loss can occur over many years and it was believed that the infected cells released more HIV particles, triggering the body to activate more T cells which in turn were also infected and killed.

But when British and American researchers from Emory University in Atlanta and the Institute of Child Health in London modeled this pattern, they found that if it had corresponded to reality, the virus would have finished its deadly deed in months, not years.

The mathematical model applied to how T cells are produced and eliminated did not support the theory of an uncontrolled cycle of T cell activation, infection, HIV production and cell destruction and the very slow pace of depletion inflicted by HIV infection.

"Scientists have never had a full understanding of the processes by which T helper cells are depleted in HIV, and therefore they've been unable to fully explain why HIV destroys the body's supply of these cells at such a slow rate. Our new interdisciplinary research has thrown serious doubt on one popular theory of how HIV affects these cells, and means that further studies are required to understand the mechanism behind HIV's distinctive slow process of cellular destruction." said co-author Professor Jaroslav Stark, from Imperial College London.

The virus could slowly adapt itself during the infection, but this theory needs to be checked.

"If the specific process by which HIV depletes this kind of white blood cell can be identified, it could pave the way for potential new approaches to treatment." said Stark.

"HIV is an incredibly complex virus and research is ongoing to try and establish exactly how it works. We need more studies in this area before we can draw any clear conclusions." said Roger Pebody, a treatment advisor at HIV charity Terrence Higgins Trust.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //