Scientists have recently used the European Space Agency's (ESA) Mars Express orbiter to study rocks that were thrown out of large craters by powerful impacts that occurred long ago. The results of their investigation revealed that the Red Planet was rich in water until about 1 billion years after forming.

In other words, from around 4.5 to 3.5 billion years ago, the Martian underground was extremely rich in the precious liquid. This discovery lends more credence to hypotheses speculating that the world may have been able to support the development of primitive lifeforms at some point.

The achievements made possible by Mars Express are all the more amazing when considering that the entire study was conducted from hundreds of kilometers above our neighboring world's surface.

Scientists have been debating about the history of water on Mars for many years, ever since missions such as the Mars Exploration Rovers and Phoenix Mars Lander established that water once flowed on the planet. Now, the debate has moved on determining exactly when this happened.

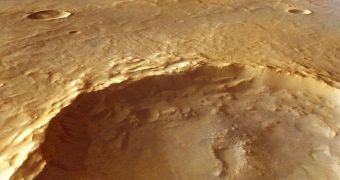

Data collected by Mars Express were augmented with readings from the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which has been surveying the Red Planet since 2006. The satellites were focused on some ancient southern highlands, called Tyrrhena Terra.

The rectangular landscape feature covers an area of about 1,000 by 2,000 kilometers (621 by 1,242 miles) and studying it has provided researchers with a wealth of new data on the Martian underground. A total of 175 sites in this region have been studied by the two spacecraft.

“The large range of crater sizes studied, from less than 1 km to 84 km wide, indicates that these hydrated silicates were excavated from depths of tens of meters to kilometers,” says the lead author of the new investigation, Damien Loizeau.

“The composition of the rocks is such that underground water must have been present here for a long period of time in order to have altered their chemistry,” the expert goes on to say.

According to study coauthor Nicolas Mangold, water circulation occurred beneath the Martian surface some 3.7 billion years ago, before the time when most of the craters formed in Tyrrhena Terra.

“The water generated a diverse range of chemical changes in the rocks that reflect low temperatures near the surface to high temperatures at depth, but without a direct relationship to the surface conditions at that time,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //