According to the conclusions of a new study published in the April 13 issue of the top scientific journal Nature Geoscience, it appears that the atmosphere around Mars was never thick enough to allow for the existence of liquid water on the Red Planet. A thick atmosphere is needed to support the greenhouse effect, which warms the surface to some extent.

Unlike Earth, which lies right in the middle of the Sun's habitable zone, Mars lies at this area's outermost boundary, just like Venus lies at its innermost boundary. This translates into Venus having a runaway global warming effect that burns the surface of the planet, while Mars is much colder than it should be. Warming phenomena worked very differently for our neighboring worlds.

The team behind the new study says that, even if Mars did feature higher temperatures at one point or another, these were just temporary. In other words, the appropriate temperatures never existed for periods of time long enough to support the development of seas, lakes, or environments where basic life might have appeared. The study was led by experts at the Princeton University in New Jersey.

Planetary scientist Edwin Kite, the leader of the research group, says that the new results point at a scenario where the lakes and seas that were at one point present on Mars were created during abnormally warm periods and were short-lived. The implication here is that the Red Planet never had a consistently-hospitable phase in its history, but rather just a series of occasional warm spells.

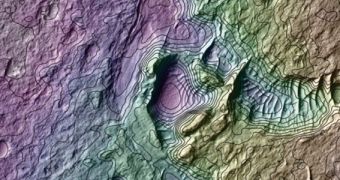

The new results are based on an analysis of 300 impact craters on the planet's surface, imaged with the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Between themselves, these craters cover an area of about 84,000 square kilometers (32,400 square miles) near the planet's equator. A series of lowlands that might have been sculpted by erosion and a few rugged canyons were also surveyed.

Around 10 percent of the studied craters were less than 50 meters (165 feet) across, while another 10 percent were smaller than 21 meters (69 feet) in diameter. This suggests that the features were created by relatively small asteroids or meteorites impacting the Martian surface. However, this scenario is incompatible with a thick atmosphere, Nature News reports.

A higher atmospheric density would have led to the destruction of many of these small asteroids long before they would have had the chance to reach the surface. A similar phenomenon happens on Earth, where numerous small meteorites are destroyed everyday as they attempt to enter our atmosphere.

The new study suggests that, at its thickest, the Martian atmosphere was never at more than 150 times its current value. This means that it was only 33 percent as dense as some researchers believe would have been required to support the presence of liquid water. “It’s clear that Mars was wet, but it’s not so clear how it was warm,” says researcher Sanjoy Som.

The expert holds an appointment as an astrobiologist with the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science in Moffett Field, California. This is, however, “an excellent paper. It bolsters previous studies that suggest early Mars was icy,” concludes planetary scientist James Head, from the Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //