A new scientific study now seeks to bring further information about the mounds identified on Martian soil, which last spring had astronomers buzzing with excitement, because they could have very well been remnants of or even active hot springs, not unlike those found at the Yellowstone national park, in the US. If that's true, we could be one step closer to learning if there is actually life on Mars, because these springs offer the perfect conditions for microorganisms to appear and develop.

In fact, it's believed that on Earth, even now, the closest relatives of the primordial forms of life can be found in areas surrounding hot springs, where the heat, humidity, and liquid water offer the ideal conditions for bacteria and other creatures to multiply and grow. Because these areas are mostly out of the influence of other factors, they can be a relative safe haven for organisms that have adapted to this environment, and actually take advantage of it.

If the same holds true on Mars, then we could be on the verge of a major find, especially considering the fact that most evidence collected of it so far seems to indicate that the Red Planet has been at some point in its history both warmer and wetter. This is also further proven by the proof that ice caps can be found even now on it, buried under a layer of rock, sand and other sediments, at both the North and the South Poles.

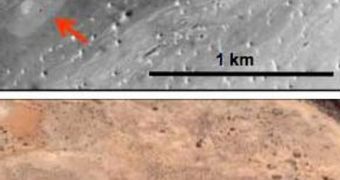

The images sent back last year by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), showed a remarkable similarity between the mounds of Mars and the hot springs on Earth, which further advanced the theory according to which the former was even at the moment capable of supporting life, even if only in its basic form. These finds are elaborated in the latest issue of the journal Astrobiology.

However, a clear conclusion cannot be yet reached at this point, simply because the Red Planet is covered in a permanent layer of dust, which is thick enough to block the spectrometers designed to measure the exact composition of the mounds. The only solution standing is direct measurement, which means that a rover must be deployed at the scene.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //