Conditions such as arthritis or severe injuries from sports could soon be treated a lot more efficiently, and maybe even cured, by a new type of scaffolding devised by experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Cambridge University. Their new material is specifically designed to boost the growth of bone and cartilage tissues, and, according to a series of articles published over the recent weeks in the Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, it can be “installed” in any type of joint, with an optimum effect. The experts who developed it say that the system performed admirably in lab tests.

“If someone had a damaged region in the cartilage, you could remove the cartilage and the bone below it and put our scaffold in the hole,” MIT Matoula S. Salapatas Professor of Materials Science and Engineering Lorna Gibson explains. She has been the co-leader of the new research, together with CU expert, Professor William Bonfield. The technology has already been licensed to British medical company Orthomimetics, which has started deploying it in clinical trials throughout Europe. The enterprise is lead by one of Bonfield's colleagues, CU expert Andrew Lynn.

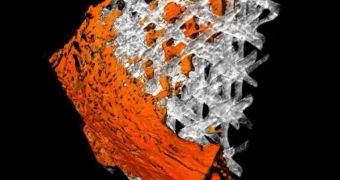

“We tried to design it so it's similar to the transition in the body. That's one of the unique things about it,” Gibson shares. The new construct is made up entirely of two layers of material, one imitating the bone, and the other one cartilages. Once implanted in a wound, they employ internal mechanisms to stimulate the mesenchymal stem cells inside the bone marrow into producing a new bone and cartilage. Until now, the research duo has only managed to create scaffolds large enough for small defects, roughly eight millimeters in diameter, but they are very confident that larger versions will soon become available.

During the preliminary studies, before the clinical ones started, the innovative technology was tested on a number of goats for approximately 16 weeks. Small holes were drilled in the animals' knees, while under anesthetics, and then the scaffold was installed to fix the damage. For the new scaffold, the team used bovine tendon as a source of collagen, added glycosaminoglycan (a type of polysaccharide chain), and enriched the mix with calcium and phosphate, so that the collagen would become mineralized.

The team, whose collaboration was made possible through the Cambridge-MIT Institute, tell that their new type of scaffold offers a cheaper, better, and less painful method of replacing damage that has happened to joints, bones and cartilages. Unlike other methods, which are very invasive and often require transplanting entire segments of cartilage from one bone to another, inserting the scaffold is a very easy procedure and does not involve harming other bones or cartilages in the process.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //