Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) announce the development of a series of algorithms that enables a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machine to conduct its scans in about 15 minutes, as opposed the 45 minutes it needs to complete a scan today.

Patients are nowadays asked many times to stay still in the MRI machine for three quarters of an hour, as the instrument collects the necessary data. Given that most people can't lie perfectly still for the entire time, the readings are imperfect and contain distortions.

This is why the study team decided to try and search for a new method of processing the vast volume of data MRI scanners return. By developing an algorithm capable of processing these information faster than ever before, the team essentially enabled the machine to complete the entire assessment faster.

MIT Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE) experts were in charge of the new effort. Details of the improvements will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

The work was led by Elfar Adalsteinsson, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and health sciences and technology at MIT, and Vivek Goyal, the Esther and Harold E. Edgerton Career Development associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the Institute.

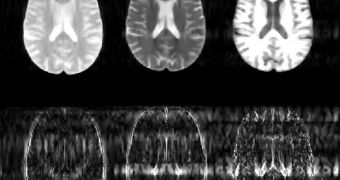

The strong magnetic fields and radio waves that MRI scanners use image the same organ and tissue many times over, producing images that exhibit slight contrast variations when compared to each other.

These small differences enable skilled radiologist to discover the development of small tumors or other unusual formations. The research group therefore had to speed up the process without affecting these important readings.

The method researchers found is innovative – use the data the scanner obtained of a particular organ during the first pass, and then use that dataset to construct the basis of the view taken during the second pass, and so on.

What the algorithm does is it enables the MRI scanner to skip having to create the image from scratch every time it passes over the location. “If the machine is taking a scan of your brain, your head won’t move from one image to the next,” Adalsteinsson explains.

“So if scan number two already knows where your head is, then it won’t take as long to produce the image as when the data had to be acquired from scratch for the first scan,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //