After a series of new observations, astronomers have finally been able to identify the origins of the galactic windstorms developing in the galaxy Messier 82. Apparently, the phenomena originate in a large number of young star clusters, and not in just a single source.

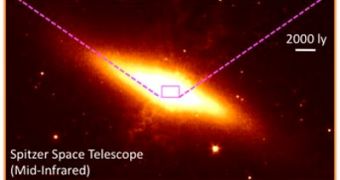

Experts even released a new set of images, showing the object in great detail. The research effort was conducted by an international team of experts, who were led by scientist Poshak Gandhi.

The investigator, who holds an appointment with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), used the powerful Subaru Telescope to carry out the new observations session. It images M82 in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Located at around 11 million light-years from our planet, Messier 82 is the closest starburst galaxy to home. Amateur astronomers can see it in the constellation Ursa Major, near the ladle of the Big Dipper.

Scientists used the Cooled Mid-Infrared Camera and Spectrometer (COMICS) instrument on Subaru for the investigations, as well as the facility's primary, 8.2-meter mirror. The tool were pointed at the core of the galaxy, where the windstorms were determined to be the most powerful.

Experts say that this super-wind is made up of cosmic dust and hydrogen gas, and that it covers an area spanning several hundreds of thousands of light-years, Universe Today reports.

Measurements conducted in past studies have shown that the winds are propelled from within M82 at speeds reaching 500,000 miles per hour. It is widely believed that this type of material makes up the basis for future star systems.

In fact, it may be that our own solar system formed from such a galactic wind, astrophysicists say. What these phenomena do is they take material from the core of the galaxy, near the black hole at the center, and then spread it out to the outer disk regions as well.

“The wind is found to originate from multiple ejection sites spread over hundreds of light years rather than emanating from any single cluster of new stars,” explains Gandhi.

“We can now distinguish ‘pillars’ of fast gas, and even a structure resembling the surface of a ‘bubble’ about 450 light years wide,” the team leader goes on to say. He adds that his group is currently trying to determine whether M82 has a supermassive black hole at its core, and whether the object is growing.

Details of the new work appear in a paper entitled “Diffraction-limited Subaru imaging of M82: sharp mid-infrared view of the starburst core,” which is published in the latest issue of the journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //