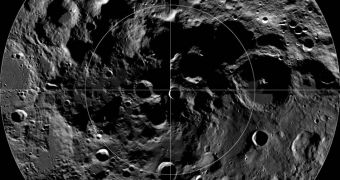

In order to be able to observed some of the most interesting (and obscured) areas of the Moon, a team of astronomers recently decided to use Lyman Alpha Emission (LAE) investigations to see permanently shadowed regions (PSR) on the lunar surface.

These areas are interesting precisely because they remain obscured at all times. Sunlight has no way of reaching them, so investigators cannot use telescope to see what's inside. The reason why they are interested in these structures in the first place is because they may contain a lot of water-ice.

This chemical would be absolutely indispensable to astronauts sent on a mission to explore the lunar surface, or establish a manned colony there. Water-ice can be used to produce liquid hydrogen rocket fuel, drinking water, breathable oxygen and other similar commodities.

But establishing the exact amounts of water ice we may expect to find on the Moon has proven tremendously difficult. A direct study conducted with an impactor spacecraft in 2009 revealed that the stuff is there, but scientists wanted to know how much was available for use.

Due to the fact that we can't simply look inside and see, a team of experts decided to use LAE analyses in order to image the water-ice deposits indirectly. With this approach does is it studies the way light is reflected off hydrogen atoms that can be found throughout the Universe.

This light – which can only be seen in a very narrow wavelength band – spread out all over the place, even hitting the concealed deposits at the bottom of PSR. “Instead of sunlight reflected straight off the craters themselves, we go an indirect route,” says Kurt Retherford.

“Our light shines off hydrogen atoms spread throughout the solar system,” he adds. Retherford is a coauthor of the new investigation, and also a senior research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, Texas, Space reports.

The investigation revealed that the rocks inside these polar craters may be “fluffier” than we've grown accustomed to seeing on the surface of the Moon. Rocks at these locations may also be more porous.

A porous texture may be the result of water particles slowly mixing with the sand, causing it to erode just underneath the surface. However, until we actually get there to see what's happening, these remain just speculations.

“One day, when an astronaut goes to these regions, we need a better sense of what they would see. Most previous measurements of water pertain to water that's very beneath the surface,” Retherford says.

“But we're really dealing with what the surface of these things looks like. The water that's there is going to be some of the more accessible stuff to astronauts in the future,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //