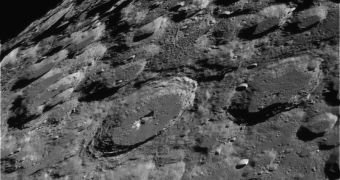

The surface of the Moon is covered with thousands of craters, some of which deeper than most of the mountains here on Earth and large enough to accommodate a few Grand Canyons. Nonetheless, NASA wants to send a manned mission back to the Moon by the end of 2020, but they hope the next trip to the Moon wouldn't be just a simple visit. Establishing a lunar base is amongst the priorities of the US space agency, however in order to do that, they must first find water.

There is evidence that there is water on the surface of the Moon, but none of the previous robotic probes discovered any in their studies. It is hoped that the next lunar probe, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter currently developed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, expected to launch by the end of this year, will gather enough data such as topography, radiation environment, temperatures and chemical composition to be used in future manned missions to the surface of the Moon, or even find direct evidence of the presence of water during its one-year mission.

Temperatures across the lunar surface are extreme. When shined by the light coming from the Sun, the surface can experience temperatures more than 100 degrees Celsius, while locations in constant darkness such as the beds of craters can cool down to temperatures of -240 degrees Celsius, cold enough to keep water in a frozen state.

During the 1990s, the Clementine and Lunar Prospector probes both found evidence of water or some substance containing hydrogen atoms in the craters near the Moon's pole. Measurements reveal that some of these craters could contain up to a cubic kilometer of water, but the collected data remains inconclusive.

"It's the job of LRO to pin that down," said Alan Stern, head of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA.

However, making measurements from a distance of 50 kilometers above the surface is extremely difficult, even for the LRO. The best scenario would be that in which all of the four instruments on-board the probe point towards the same location where water could exist. "I expect that LRO will really answer the question of whether there's water ice at the pole once and for all," said Richard Vondrak, LRO project scientist.

One of the easiest methods to check for the existence of water on a body such as the Moon would be to simply look into these craters and see if any ice is present there. Albeit, on the Moon there is no diffuse light reflected from the atmosphere, thus the shadows there are even darker than those on Earth.

The LRO probe will look for water by using an illumination method involving the light of background stars. The light reflected by the crater beds is then captured by the Lyman-Alpha Mapping Project, which is specially designed to detect ultraviolet wavelengths. Not only are distant stars much brighter in the ultraviolet spectrum, but water also creates a unique signature when reflecting ultraviolet light.

Additionally, the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter on-board the LRO will map the contours of the lunar surface by shinning it with a beam of laser, which can also reveal whether or not any ice crystals are present there through the brightness of the reflected light collected by the LRO probe.

Water and water ice, as well, have the unique ability of absorbing neutrons (water and heavy water is used as moderators in nuclear reactors). Thus, the Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector will analyze the density of neutron radiation reflected back into space by the lunar surface.

Last but not least, the Diviner instrument will have the role to create a map of the lunar surface in relation to thermal variations, including permanently shadowed craters. Diviner will also have the role of showing that these crater beds are cold enough to keep water in a frozen state.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //