Japanese researchers have managed to recently bring new hope to the millions of people worldwide suffering from tooth conditions such as cavities, when they succeeded in artificially conditioning mice into developing new teeth to replace the ones they'd lost. The method does not rely on implanting artificial prosthetics, but rather on offering the triggers required for new ones to grow on their own. The team behind the achievement says it's now working on a method to translate the discovery to humans.

The experts oriented their efforts on tooth germs, which are the formations from which actual teeth grow during development. All the scientists are from the Tokyo University of Science, in Noda, Chiba Prefecture, and were led by cell biologist Takashi Tsuji, ScienceNow reports. They extracted tooth germs from undeveloped mouse embryos, and then separated them into epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells. After recombining the cells with a twist, they managed to obtain fully functional teeth within 49 days from the implantation in bare rodent jaws.

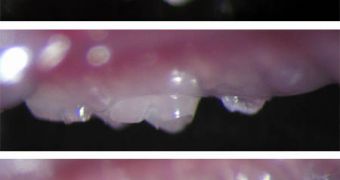

In a study published online yesterday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the team reports that the tooth germs, implanted in place of an extracted molar, were first off cultivated in a separated culture for five to seven days. Some 36 days after the procedure took place, the new teeth started making their way through the gums, and, 49 days into the study, they aligned themselves properly with the other teeth, and could be used to consume rough food. The team emphasizes the fact that there is no difference between the new and the old teeth.

The “freshly hatched” ones have pulp, roots and a protective outer enamel layer, and are just as tough as the other ones. Additionally, they also developed periodontal ligaments, which are the things that bind the tooth to the jaw bone, and also nerve fibers. These fibers give a feeling of the pressure applied on hard foods when chewing, something that is unheard of in fake prosthetics. “We clearly demonstrated that the bioengineered organ germ could develop into a fully functioning organ,” Tsuji says of the accomplishment.

“This is a significant advancement. [...] It is the first time that it is demonstrated that starting from [just two cell types] an extracted tooth can be replaced,” University of Helsinki developmental biologist Irma Thesleff shares, adding that, indeed, the Japanese group built their advancements on previous work, but that the credit for the discovery was all theirs for the innovation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //