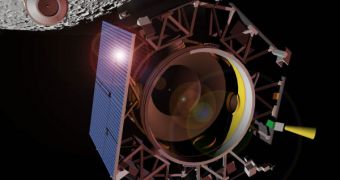

The Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) instrument recently gave its mission controllers quite a fright, when it had to perform some emergency maneuvers, in order to maintain its correct course. The unplanned movements took up almost half of the craft's remaining fuel, and mission controllers are now desperately looking for a solution to keep the satellite and its Centaurus spent rocket stage segment on the correct path, Space reports.

LCROSS is designed to carry the rocket segment around until October 9th, when it is scheduled to drop it in a dark crater and photograph the impact. Hopes are the plumes of dust and rocks that will be generated once the 41-foot stage crashes will reveal signs of frozen water on the Moon. Telescopes on Earth and special instruments aboard the LCROSS will be aimed at the plume. Experts hope to be able to use spectrometers to divide the frequencies of light that will be captured, and then hopefully identify the one that ice water makes.

Ames Research Center expert Dan Andrews, the mission's project manager, said that the craft had to consume 140 kilograms, or 309 pounds, of maneuvering fuel in its peculiar trek through space on Saturday, just to maintain its orientation. “Our estimates now are if we pretty much baseline the mission, meaning just accomplish the things that we have to (do) to get the job done with full mission success, we're still in the black on propellant, but not by a lot,” the expert told Spaceflight Now.

NASA is considering the mission to be risk-tolerant, which means that there is a moderate possibility that the craft and its cargo will never complete their primary assignment. Engineers at Ames have now reduced the sensitivity of the guidance system, which means that, if further glitches appear in the future, the craft won't spend that much fuel trying to correct them automatically. “For example, if we find that the spacecraft in [sic.] inclined to do a bunch of thruster firing activity, or if we notice one of the key avionics elements failed, we would rather go into a free drift than expend a bunch of propellant and seal our fate,” Adrews explains.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //