As a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck Japan on March 11, American and European satellites were monitoring the Pacific Ocean, looking for signs of tsunamis. In addition to seeing the waves develop and wipe out the country's coastlines, they also saw the first-ever hints of a merging tsunami.

Such a natural event was proposed to exist years ago, but researchers could never get sufficient data to confirm their suspicions. What separated a normal tsunami from a merging one is the fact that the latter has its destructive power amplified when passing over rugged ocean ridges.

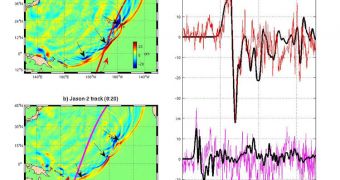

Investigators with NASA and the Ohio State University (OSU) say that their data clearly show merging tsunamis to be an actual phenomenon. This was made obvious by radio imagery from satellites belonging to NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA).

At the same time, it was also found that the earthquake triggered two wave fronts in the water on March 11. Eventually, they merged together to form a double-high wave, even as the structure was traveling far off the coastlines.

At great distances, tsunamis are expected to lose at least some of their power, but this one did not, precisely because of the aforementioned merger. Simultaneously, undersea mountains and ridges in the tsunami's path focused its energy along certain directions.

The land areas that were directly on these directions were the ones that were the most affected, experts say. The image that is currently emerging about this disaster is that a lot of factors that have never even been considered before contributed to the disaster.

The new data can also be used to describe how the tsunami caused massive damage at certain locations alongside Japanese coastlines, while others were left largely untouched. In the end, the knowledge may be used to improve tsunami forecast methods and models.

“It was a one in 10 million chance that we were able to observe this double wave with satellites,” says Y. Tony Song, a research scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California. He was also the principal investigator on the new research.

“Researchers have suspected for decades that such 'merging tsunamis' might have been responsible for the 1960 Chilean tsunami that killed about 200 people in Japan and Hawaii, but nobody had definitively observed a merging tsunami until now,” the expert says.

“It was like looking for a ghost. A NASA-French Space Agency satellite altimeter happened to be in the right place at the right time to capture the double wave and verify its existence,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //