A group of engineers in the United Kingdom, at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL), have begun subjecting one of the instruments that will go on the JWST to space-like conditions.

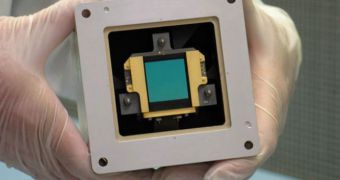

The Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) is one of the critical components of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is touted as the replacement for the venerable Hubble Space Telescope.

At this time, it is scheduled to launch a few years from now, and it will represent the most advanced piece of hardware ever deployed to space.

But before this can happen, experts need to ensure that all of its components are ready to fly. And RAL facilities are indispensable for this purpose.

“The start of space simulation testing of the MIRI is the last major engineering activity needed to enable its delivery to NASA,” explains scientist Matt Greenhouse.

“It represents the culmination of 8 years of work by the MIRI consortium, and is a major progress milestone for the Webb telescope project,” adds the expert, who is the NASA Project Scientist for the Webb telescope Integrated Science Instrument Module.

Greenhouse is based at the American space agency's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), in Greenbelt, Maryland. He explains that the JWST has a long road ahead.

Unlike Hubble, which is placed in orbit around the planet, James Webb will need to reach the L2 orbital point, an area of space located some 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth.

“We’d like to try and identify very young galaxies, containing some of the first stars that formed in the Universe,” explains Gillian Wright of the mission the MIRI will have.

“MIRI is absolutely essential for understanding planet formation because we know that it occurs in regions which are deeply embedded in dust,” he goes on to say

Wright is the European Principal Investigator for MIRI, and he is based at the UK Astronomy Technology Center, in Edinburgh, UK, Space Fellowship reports.

Developed jointly by NASA, ESA and the Canadian Space Agency, the telescope will need to be able to support some extreme conditions, and researchers want to ensure that this is possible.

Hence the need to have the MIRI checked out at RAL. Facilities here enable scientists to simulate extremely low temperatures, that are similar to the ones the JWST will be battered with in space.

The observatory will also have to deal with massive amounts of radiation pouring in on it, but scientists are convinced that its revolutionary heath shield will help it in that regard.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //