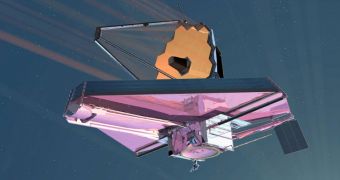

Officials at the American space agency say that Hubble's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, will not launch before 2018. However, when it does take off, the instrument will allow us to search for small extrasolar planets around distant stars.

The observatory is being put together in order to unlock some of the greatest mysteries in the Universe, including how the earliest stars and galaxies developed, how black holes work, what neutron stars are, and so on. But it also has a huge potential for use in exoplanetary research.

Exoplanets are worlds located outside our solar system. The NASA Kepler planet-hunting telescope already identified 2,325 candidates, and about 61 confirmed ones, and it hasn't even reached the end of its mission. The JWST could be used to drastically augment these numbers.

When deployed to space, the telescope will fly to the Lagrange 2 orbital point. From this location, some 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth, the spacecraft will always remain in the same relative position with respect to the Earth-Sun-Moon system.

The $8.8 billion observatory will be able to look at a much wider patch of sky than Kepler currently covers. Most of the stars in the Kepler field of view are very far away, and crammed inside a very small portion of the night sky.

The JWST can be pointed at multiple locations, potentially even towards some stars that are bright, and located nearby. If the telescope manages to find exoplanets around these objects, then it may be possible to use its sensitive infrared instruments to study their atmosphere.

This can be done with the Hubble Space Telescope today, but the famed observatory can only analyze gaseous envelopes surrounding gas giants. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) astronomer David Charbonneau says that the JWST could analyze the atmosphere around Earth-like exoplanets.

This would be the Holy Grail of exoplanetary research – finding a rocky planet the size of Earth around a nearby star, and then analyzing the chemical composition of its atmosphere using precise instruments.

In addition, the telescope will cover a gap in current space observatory capabilities. “For one thing, Webb will be able to go beyond the reach of Hubble and Spitzer because they're too small. Spitzer is infrared, but it has a tiny mirror,” Charbonneau tells Space in an exclusive interview.

“Hubble has a good size mirror but not the infrared sensitivity. The other major problem with Hubble is its orbit – we have gaps in data because of Hubble's orbit,” the CfA astronomer concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //