Bioplastics, plastics that can degrade over time, like naturally occurring substances, have been an increasingly important field of study for various reasons, so it is not a surprise to hear about 3D printing technology trying to incorporate them.

We actually heard about attempts at making biodegradable 3D printing materials before, but the numbers of bioplastics compatible with this method of manufacture remains small.

Fortunately, there are plenty of scientists around the world doing their best to provide greener alternatives to oil-based plastics, thus reducing pollution and alleviating a host of other negative effects of human technological, building and fabrication techniques.

One such team is composed of researchers from the Italian Institute of Technology. The members are Athanassia Athanassiou, José Alejandro Heredia-Guerrero, Luca Ceseracciu, Francesca Pignatelli, Roberta Ruffilli, Roberto Cingolani, Ilker S. Bayer, and Susana Guzman-Puyol.

With 3D printing, it's not so much the prints themselves that do harm, but the leftover plastic and scaffolding material.

PLA, or polyactic acid, may be biodegradable, as it is derived from tapioca, sugarcane and corn starch, but other plastics are not. Also, ABS plastic is more flexible and has a higher temperature resistance, which is why PLA is passed over in favor of it, despite the environmental unfriendliness.

What the research team did was come up with ways to make plastic from vegetables, as odd as it sounds. Rice, parsley and spinach are all being studied. Cocoa is another plant of interest.

The bottom line is that using organic, naturally occurring acid like TFA (Trifluoroacetic acid, a colorless liquid with a sharp odor, similar to vinegar, but stronger), the scientists were able to process cellulose. Cellulose is the main substance that gives plants their solidity, flexibility and tensile strength.

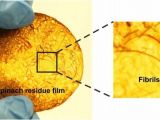

First, the TFA acid was mixed with the vegetables we mentioned, then the scientists poured the mixture into petri dishes and waited. After a while, films formed, each with different physical attributes. Some were rigid and brittle, other softer and flexible. What they all had in common, however, was that they behaved like petroleum-based plastic.

All these findings were published in the ACS journal, Macromolecules, and will probably become the basis for many filament spools in the not too distant future. It might take a year or so, but by this time in 2015 we may see oil-based filament being sidelined by greener but no less expensive alternatives. We can hope for such an outcome at least.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //