A natural human protein could be a potential treatment for this fatal genetic disease, since a latest research showed that the key protein biglycan can slow down muscle damage and improve function in mice with the genetic mutation that causes muscular dystrophy.

A paper published online describes the experiments carried out by Justin Fallon, professor of neuroscience at Brown University and the senior author, and his team.

It says that biglycan delivered to the bloodstream draws utrophin to muscle cells' cellular membranes, and the protein works to help the cells build and retain their strength, just like it does when it is present in fetuses, infants and toddlers.

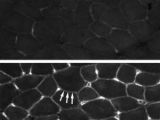

One of the experiments, ended with a 50% reduction in “centrally nucleated” fibers in the muscle tissue of biglycan treated mice – fibers are known to be indicators of recent tissue damage and repair, so when they are reduced, this means that the muscle tissue is less damaged.

The researchers also put mouse muscle through a standard stress test, where they are stretched and contracted at the same time.

What is interesting about it, is that the test ultimately weakens even healthy muscle, but in this case, the biglycan-treated muscles of mice with muscular dystrophy, lost their strength 30 percent slower than similar untreated mice.

A couple of months ago, the start-up company Tivorsan Pharmaceuticals licensed rights from Brown to biglycan, with the goal of bringing the potential therapy through clinical trials.

Biglycan restores the muscle-strengthening presence of a protein called utrophin, that mostly exists in very young children.

Fallon carried out many series of tests and in the most recent ones, after using an improved formulation of biglycan, the treated muscles lost their strength up to 50% slower than untreated ones, which means that mice treated with the protein are holding on to more of their function for a longer time.

Another encouraging thing is that it seems that the effects of treatment with biglycan lasted through months of testing, and there were no signs of harmful side effects.

As biglycan seems to be effective in the mouse model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Fallon says that “the next big step is testing in humans,” hoping that it can improve the lives of thousands of children.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy is a fatal genetic mutation that affects about one of every 3,500 boys, who are unable to produce the necessary dystrophin to keep muscles strong.

By eight years of age, the boys start to have difficulties walking, a couple of years later they are often in wheelchairs, and by their 20s they die from degraded muscle function.

“This is all aimed at getting a therapy that will meaningfully improve the condition of patients,” said Fallon

“This is an important step along that path.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, Charley’s Fund, the Nash Avery Foundation, and Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, and a paper describing it was published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //