Undoubtedly, when our ancestors first climbed down of their respective trees, learning to survive on the ground was something that they had to do very fast, or perish. As such, learning to throw things very far and accurate turned out to be a great trait. Experts now show its neural mechanisms.

Throwing objects at a long distance is one of the things that are uniquely humans. People standing on the shores of a lake simply feel the urge to pick up a stone and throw it as far as possible. The same holds true for snowballs as well.

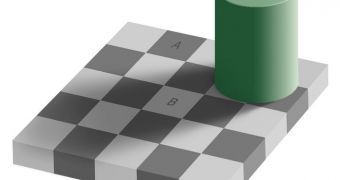

According to a new scientific study, this ability that most likely helped our evolutionary ancestors considerably stems from an illusion, which is known among experts as the size-weight conundrum.

This basically states that a person holding two objects of equal weights but different sizes will always consider the larger object to be lighter. Experts at the University of Wyoming and the Indiana University now say that this illusion may play a critical role in underlying our ability to learn to throw things far.

It could be that this illusion is giving children in their earliest stages of development an edge over other animals, by helping them learn how to select the most suitable object for a specific type of throw.

“These days we celebrate our unique throwing abilities on the football or baseball field or basketball court, but these abilities are a large part of what made us successful as a species,” explains researcher Geoffrey Bingham, quoted by Science Blog.

“It was not just language. It was language and throwing that led to the survival of Homo sapiens, and we are now beginning to gain some understanding of how these abilities are rapidly acquired by members of our species,” he adds.

The expert holds an appointment as a professor in the Indiana University Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. He says that our species, Homo sapiens, prevailed due to three main qualities: social organization and cooperation, language, and the ability to throw stuff.

The latter is what allowed our ancestors to make it through the Ice Age. The only food sources available were very large animals such as mammoths and sloths, and early humans had to use their spears in order to put them down.

Without the ability to throw objects at a distance, our ancestors would have starved to death during the Ice Age, and would have had no material from which to manufacture clothes.

“The idea here is that our speech and throwing capabilities came as a package. Language is special, and we acquire it very rapidly when young,” Bingham explains.

“Recent theories and evidence suggest that perceptual biases in auditory perception channel auditory development, so that we become attuned to the relevant acoustic units for speech,” he adds.

“Our work on the size-weight illusion is now suggesting that a similar bias exists in object perception that corresponds to human readiness to acquire throwing skills,” concludes the expert, who is also the director of the Perception/Action Lab at IU.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //