The IBM Corporation has officially entered the lab-on-a-chip market, with the development of its first microfluidic device. Their new instrument could offer a potent diagnostics tool against numerous diseases and virus types, as it makes use of capillary action to draw its conclusions. According to the company, the tool only requires a small drop of blood to operate and the results are almost always to the point, Technology Review reports.

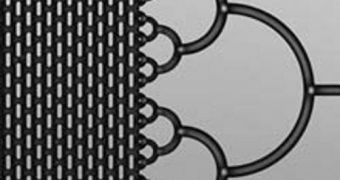

The device is, of course, filled with tiny channels, which draw in the drop of blood and then pass it through intricate networks of smaller channels. The chip itself is laden with numerous markers that react to the pathogens creating a large number of medical conditions and the results are then displayed within 15 minutes, representatives from IBM say. One of the co-developers of the new device is Emmanuel Delamarche, a scientist with the IBM Zurich Research Laboratory, in Switzerland.

University Hospital Basel researcher Luc Gervais, who also works for IBM says that one of the main advantages the new instrument has is the fact that it features no moving parts. Rather than employing an active blood-sorting method, it uses capillary action to separate blood in its components and then pump it through the various arrays of channels that make up its interior. At this point, “there is a trend toward this sort of moving-part-free device,” explains microfluidic expert Jikui Luo. He holds an appointment with the University of Bolton Center for Materials Research and Innovation, in the UK.

Another advantage of the new instrument is the fact that it can test for multiple conditions at the same time and display all its results at once, the IBM team highlights. Other similar devices can only be manufactured to produce results that confirm or infirm the existence of a single disease in the blood or water samples. “If a patient has just had a heart attack, a yes or no test is not going to help determine the best course of action. This [chip] pushes point-of-care diagnostics to the next level,” adds Gervais.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //