Apparently, scientists have taken quite a liking to toying with cells and getting them to do things that are not included in their working agenda. The end goal of such experiments is the development of new treatment options for all sorts of conditions.

Not to beat about the bush, a recent paper in the journal Circulation details the use of human scar cells to improve blood flow in mice by having them quit their regular job and get busy forming blood vessels instead.

The experiments, carried out by Houston Methodist researchers, are expected to pave the way for a new method to repair damaged tissues in living organisms by improving blood flow, oxygenation and even nutrition.

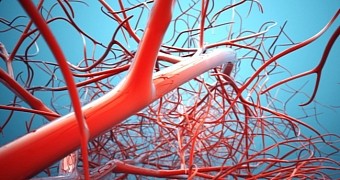

Turning scar cells into blood vessel cells

Writing in the journal Circulation, the Houston Methodist specialists who conducted these experiments explain that, as part of this research project, they started by collecting a special type of human scar cells known as fibroblasts.

These cells play a crucial role in wound healing processes, and can be found all throughout the human body. Once exposed to several compounds, an acid and various growth factors included, the scar cells turned into endothelial cells.

As detailed by the Houston Methodist researchers, endothelial cells form the lining of blood vessels. Hence, the scientists argue that the outcome of these experiments goes to show that, all things considered, it is possible to use scar cells to grow blood vessels.

Although just 2% of the fibroblasts the specialists toyed with turned into endothelial cells, the study is nonetheless hailed as a breakthrough. More so given the fact that, according to evidence at hand, a transformation rate of 15% is well within reach.

“That's about where we think the yield of transformed cells needs to be. You don't want all of the fibroblasts to be transformed – fibroblasts perform a number of important functions, including making proteins that hold tissue together.”

“Our approach will transform some of the scar cells into blood vessel cells that will provide blood flow to heal the injury,” study principal investigator and Houston Methodist Research Institute Department of Cardiovascular Science Chair John Cooke said in a statement.

Putting the engineered cells at work

It is understood that, apart from compelling the human scar cells to change and assume an entirely different role, the scientists also transplanted some of the endothelial cells they obtained during these experiments in laboratory mice.

The rodents that were transplanted the endothelial cells were suffering from poor blood flow to their back limbs at the beginning of the study. However, not too long after the engineered cells were introduced into their bodies, they started feeling much better.

“The cells spontaneously form new blood vessels – they self assemble,” said John Cooke. Furthermore, “Our transformed cells appear to form capillaries in vivo that join with the existing vessels in the animal, as we saw mouse red blood cells inside the vessels composed of human cells.”

The researchers hope that, in time, their work will help pave the way for the development of new and more effective ways to treat cardiovascular damage and all sorts of other injuries. Still, they say that, before they can even think about rolling out clinical trials involving human patients, they must carry on experimenting on animals for a while longer.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //