The human nervous system acts like a giant supercomputer, encoding everything the body does or could do, researchers say. Limb motion is no different from all our other systems, they add, so understanding its correlations to the brain could lead to advancements in numerous areas of medicine. Now, researchers reveal that a key feature of this encoding plays a massive part in how new motor skills are learned and memorized in the brain. The finding could have considerable implications for the creation of new therapies meant to promote stroke recovery.

The goal of such treatments is to encourage new motor adaptation in stroke patients, a fact that would conceivably reduce healing times, and restore basic functions in the patients' bodies. The more healthcare experts know about the neural learning elements that promote motor learning, the more they could improve on these recovery methods, researchers at the Harvard University say. Details of their most recent work appear in the November 25, 2009 issue of the respected scientific journal Neuron.

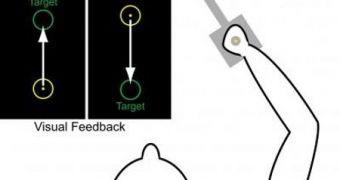

The position and velocity of limb motion were initially things that researchers thought were encoded as independent variables. Since then, studies have shown that the two are actually encoded in a positively correlated manner, mostly by the brain's primary motor cortex, and the body's low-level peripheral stretch sensors. “While this correlation between the brain's encoding of the position and the velocity of motion is well-known, its potential importance and practical use has been unclear until now,” scientist Maurice A. Smith, a coauthor of the Neuron paper, explains. He is an assistant professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and also holds an appointment in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Center for Brain Science.

“In stroke rehabilitation, patients who make a greater effort to use their impaired limbs can achieve better outcomes. However, there is often a vicious cycle, as a patient is far less likely to use an impaired limb if his or her other limb is fine. This pattern slows recovery and leads to greater impairment of the affected limb,” the expert reveals. The investigation was supported by grants from the McKnight Endowment for Neuroscience, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation. Experts from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the King's College London, in the UK, were also a part of the work.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //