Investigators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, have recently managed to shed new light on the complexities of cognitive comparisons we conduct innately. The insights go against previously established wisdom, the group says.

Comparing single items is a relatively easy and straightforward process. We look at the properties of the two objects or phenomena being compared, and decide which of them best suits a set of control criteria. However, comparing sets or groups of objects is not that easy.

The MIT team gives that example of the Rockies and the Alps, both large mountain chains. The Alps are higher and feature the tallest peaks, but the Rockies have more peaks and span over a greater area. So which of them is the largest? The issue is very complex.

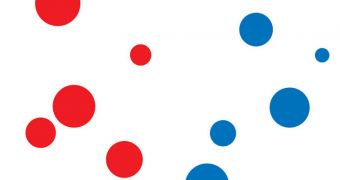

According to MIT Department of Linguistics and Philosophy PhD student Peter Graff, “plural comparison follows from comparing every individual in one set with every individual in another set.” He says that this is how scientists used to interpret comparisons between sets of objects.

However, the new work he and his colleagues have conducted indicates that this is not the case. Apparently, “plural entities are represented as entities with their own properties,” the expert says. Details of the study were published in the latest issue of the esteemed scientific journal Cognition.

What this implies is that our minds unconsciously choose some line of comparison, and then compare the groups as single entities, based on those criteria. “You can ascribe a property to a plurality, namely an average statistic, which may not necessarily be true of any of its members,” Gregory Scontras says.

The expert, a coauthor of the paper, is a PhD student in linguistics at the Harvard University, in the US. Other investigators say that the research is very promising, and definitely worth pursuing.

“This work is important because it shows that very abstract conceptual principles guide how we organize and store basic perceptual information,” comments University of California in San Diego psychology professor, David Barner.

“Logical models of reasoning and language since Aristotle have treated individuals as fundamental, and so you might think that all sentence meanings could be described building up from statements about individuals,” he adds.

“This work suggests that language may be more clever than this, and may allow us to create complex things, or ‘plural objects',” concludes the expert, who was not part of the research team.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //