Experts with the Scripps Research Institute, in Florida, say they have made significant progress in understanding how we forget things. The biology underlying this process has remained a mystery for years, despite scientists' best efforts to unravel it.

What made matters worse was the fact that forgetting has been with our species since we first evolved. It is exacerbated by conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer's, but experts were unable to find out exactly how the process occurs. What they did was propose a few reasons why the process exists.

The SRI team found in a new study that the same mechanism that is essential to the formation of new memories is also responsible for destroying other memories. Primarily, the research group focused on the molecular biology of active forgetting.

For many years, scientists have operated under the presumption that forgetting is a passive process, but that view is slowly beginning to change now, in light of numerous new studies showing otherwise.

“Until now, the basic thought has been that forgetting is mostly a passive process. Our findings make clear that forgetting is an active process that is probably regulated,” says the chair of the SRI Department of Neuroscience, Ron Davis, also the leader of the project.

Investigators focused their attention on fruit flies, a model organism that is oftentimes used to study memory in humans. After conditioning the flies in a classic, Pavlovian manner, the team analyzed how the tiny insects remembered or forgot the information, PsychCentral reports.

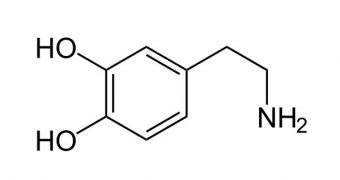

The acquisition of new memories, and the forgetting of old ones, was found to be regulated by a pair of dopamine receptors. The neurotransmitter also underlies the forgetting mechanisms, although the team says that this occurs only if no important “meaning” is attached to the memories targeted for deletion.

SRI scientists also uncovered that different types of dopamine-releasing neurons are targeting different receptors, called dDA1 and DAMB, which are both included in a tight neural network demonstrated to be involved in memory and learning.

When dDA1 is activated, new memories begin forming. If dopamine binds to DAMB, then memories are deleted. The new findings could be used to address a series of mental disorders where forgetting is a key feature.

People suffering from savant syndrome, for example, “have a high capacity for memory in some specialized areas. But maybe it isn’t memory that gives them this capacity, maybe they have a bad forgetting mechanism,” Davis explains.

“This also might be a strategy for developing drugs to promote cognition and memory – what about drugs that inhibit forgetting as cognitive enhancers?” the expert adds. Details of the study were published in the May 10 issue of the esteemed medical journal Neuron.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //